Why Traditional Bioequivalence Metrics Fall Short

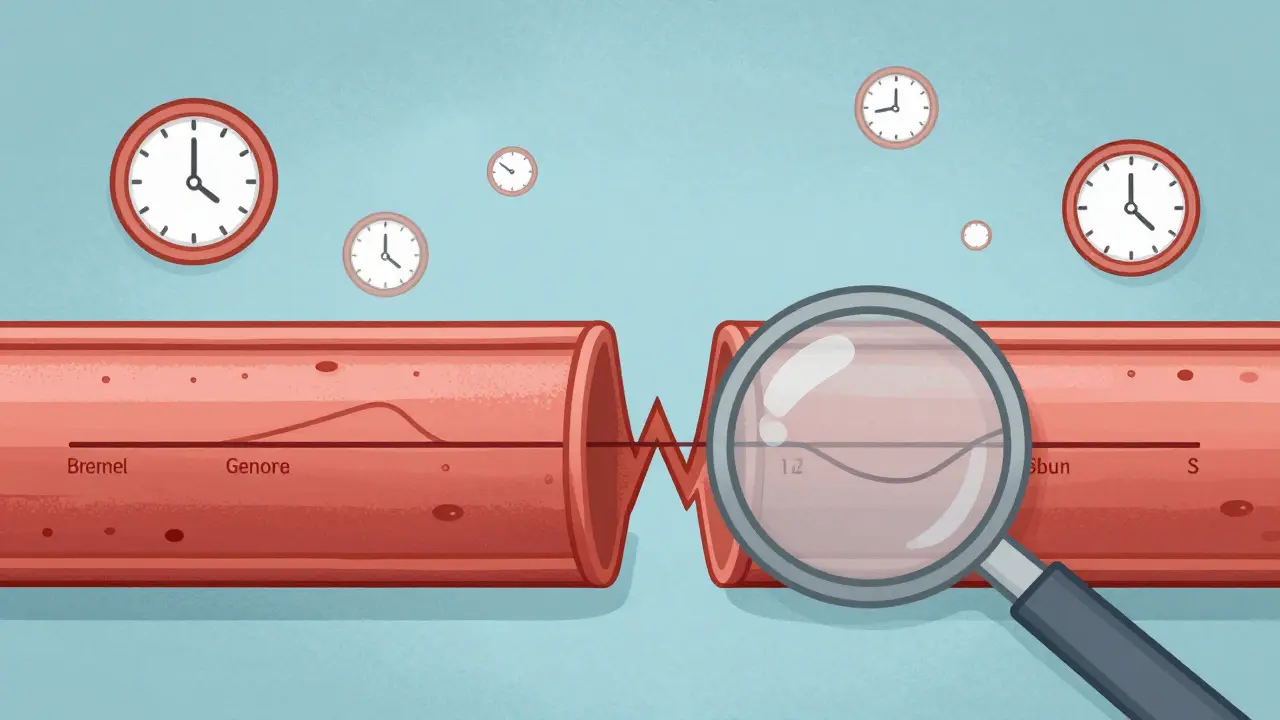

For decades, generic drug makers relied on two simple metrics to prove a drug worked like the brand-name version: Cmax (the highest concentration in the blood) and total AUC (the full area under the concentration-time curve). These numbers told regulators whether the generic delivered the same total amount of drug and reached peak levels at roughly the same time. But for certain complex drugs-especially extended-release pills, abuse-deterrent opioids, or combination formulations-these metrics weren’t enough. Two products could have identical Cmax and total AUC, yet one might release the drug too slowly in the first hour, or too fast in the first 30 minutes. That small difference could mean the difference between effective pain relief and a dangerous spike in blood levels.

Take a long-acting opioid painkiller. If the generic version releases 20% less drug in the first 2 hours, a patient might not get relief when they need it most. But if it releases 30% more in that same window, the risk of overdose goes up. Traditional AUC averages out those early spikes and dips. It sees the whole curve and says, "Same total dose, so we’re good." But that’s not how the body works. The first few hours after dosing are often the most critical for safety and effectiveness. That’s where partial AUC comes in.

What Is Partial AUC (pAUC)?

Partial AUC, or pAUC, is a pharmacokinetic measurement that looks only at a specific window of time during drug absorption-not the whole curve. Instead of measuring exposure from zero to infinity, you pick a clinically meaningful interval, like 0-1 hour, 0-2 hours, or until the reference product hits its peak concentration. You then calculate the area under the curve just for that slice.

This isn’t just a fancy math trick. It’s a targeted tool. The FDA and EMA use it to catch differences in how quickly a drug gets into the bloodstream, especially when that speed affects how well the drug works or how safe it is. For example, in abuse-deterrent formulations, the goal is to prevent crushing or dissolving the pill to get a fast high. If the generic releases drug too fast in the first 30 minutes, it might still be abusable-even if the total exposure over 24 hours matches the brand. pAUC catches that.

According to FDA documentation from 2017, pAUC is designed to be sensitive to differences in regions where drug concentrations are high-like the absorption phase-and less sensitive where concentrations are low, like the elimination phase. That’s exactly what you want: focus on the part that matters clinically.

How Is pAUC Calculated? It’s More Complex Than You Think

There’s no single way to define the time window for pAUC. The FDA allows several approaches, and the choice depends on the drug and its intended use:

- Based on a fixed time interval, like 0-1 hour or 0-2 hours

- Based on the time when the reference product reaches its peak concentration (Tmax)

- Based on a percentage of Cmax, such as the time until concentration drops to 50% of the peak

- Based on when concentrations exceed a certain threshold (e.g., above 10% of Cmax)

Each method has pros and cons. Using Tmax is common because it’s tied to the actual drug’s behavior in the body. But if subjects have wildly different Tmax values-some peak at 1 hour, others at 4 hours-then the composite curve becomes messy. That’s why the FDA recommends using reference product data from pilot studies to define the window. It’s not guesswork; it’s evidence-based.

Once the window is set, the math is straightforward: integrate the concentration-time curve over that interval. But the analysis isn’t. You can’t just plug numbers into Excel. You need to ln-transform the data, run ANOVA models, and calculate a 90% confidence interval for the test-to-reference ratio. The standard bioequivalence limit still applies: the 90% CI must fall between 80% and 125%. But now you’re applying it to a slice of the curve, not the whole thing. And that slice? It’s often noisier. That means you need more subjects.

Why pAUC Is Changing the Generic Drug Game

The shift to pAUC isn’t theoretical-it’s already reshaping how generics are developed and approved. In 2015, only 5% of new generic drug applications included pAUC. By 2022, that number jumped to 35%. The FDA now has over 127 product-specific guidances that require pAUC analysis. These aren’t suggestions. They’re mandatory.

Here’s what’s happening in real-world development:

- Extended-release opioids: The FDA now requires pAUC for 0-1 hour and 0-2 hours to ensure abuse deterrence isn’t compromised.

- Cardiovascular drugs: For drugs like extended-release verapamil, pAUC over 0-4 hours is used to match the original drug’s smooth release profile and avoid blood pressure spikes.

- CNS drugs: In antidepressants and antipsychotics, early exposure affects how fast patients feel relief. pAUC helps ensure the generic doesn’t delay onset.

One case study from the 2021 AAPS meeting showed a generic version of a psychiatric drug had identical total AUC and Cmax to the brand. But pAUC over 0-2 hours revealed a 22% lower exposure in the critical early window. The product was pulled from consideration. Without pAUC, that difference would’ve gone unnoticed-and patients could’ve been underdosed.

The Hidden Costs and Challenges

For every success story, there’s a painful one. Implementing pAUC isn’t cheap or easy.

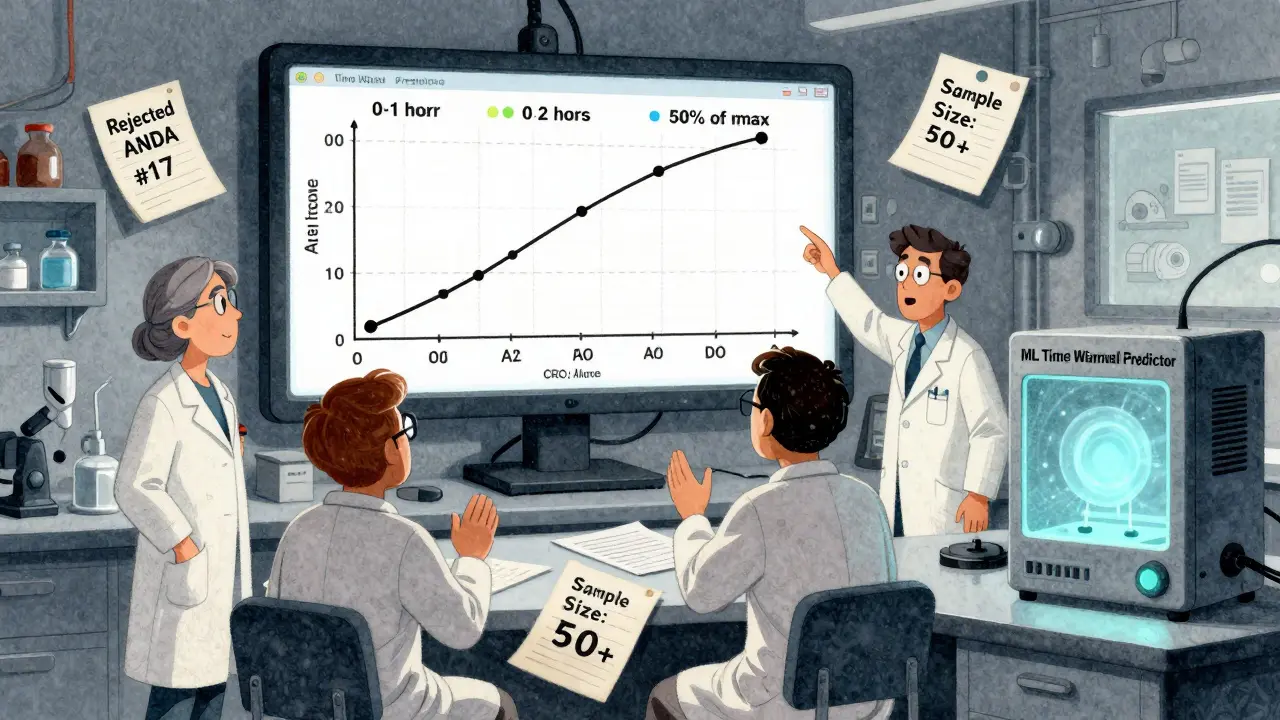

A senior biostatistician at Teva reported that switching to pAUC for an extended-release opioid generic forced them to increase their study size from 36 to 50 subjects. That added $350,000 to development costs. Why? Because pAUC measurements are noisier. The early absorption phase has higher variability between individuals. To maintain statistical power, you need more data.

And it’s not just about sample size. The lack of standardization is a nightmare. One product-specific guidance says to use 0-1 hour. Another says to use the time to 50% of Cmax. A third says to use the reference product’s Tmax. Generic developers don’t know what to do until they read the specific guidance for their drug-and even then, it’s often vague. A 2022 survey found only 42% of FDA product-specific guidances clearly explained how to define the time interval.

Between 2021 and 2023, the FDA rejected 17 ANDA submissions solely because of incorrect pAUC time window selection. That’s 8.5% of all bioequivalence-related deficiencies that year. And 63% of generic drug companies now say they need extra statistical help for pAUC-compared to just 22% for traditional metrics.

Who’s Using pAUC-and Who’s Struggling?

Adoption isn’t equal across the industry. Large pharmaceutical companies with in-house PK modeling teams and dedicated biostatistics departments are adapting fast. Smaller firms? They’re falling behind.

92% of pAUC implementations happen in companies with more than 500 employees. Smaller developers are increasingly outsourcing to specialized contract research organizations (CROs). Companies like Algorithme Pharma have built proprietary pAUC analysis tools and now control 18% of the complex generic BE study market.

Therapeutic areas with the highest pAUC use? Central nervous system drugs (68%), pain management (62%), and cardiovascular agents (45%). These are the drugs where timing matters most. If you’re developing a generic for a diabetes medication with a flat, slow release profile? You might not need pAUC yet. But if you’re working on a fast-acting insulin or a seizure drug with narrow therapeutic windows? You absolutely do.

What’s Next for pAUC?

The FDA is pushing forward. In January 2023, they launched a pilot program using machine learning to automatically determine optimal pAUC time windows based on historical reference product data. Instead of relying on subjective expert judgment, the algorithm will suggest cutoff times based on patterns across hundreds of previous studies.

By 2027, Evaluate Pharma predicts that 55% of all new generic approvals will require pAUC-up from 35% in 2022. That means nearly every complex generic drug will need this analysis.

But global harmonization is lagging. The International Consortium for Innovation and Quality in Pharmaceutical Development found inconsistent pAUC rules across the FDA, EMA, and Health Canada add 12 to 18 months to global drug development timelines. A company might design a study for the U.S. using 0-2 hours, only to find the EMA requires 0-1 hour. They have to run two separate trials. That’s expensive. That’s slow.

Still, the science is solid. As the FDA’s 2021 white paper put it: "The principles and rationales for using pAUCs are scientifically sound and necessary to ensure therapeutic equivalence for certain drug products where traditional metrics fall short."

How to Get Started With pAUC

If you’re a generic developer, regulator, or researcher, here’s how to begin:

- Check the product-specific guidance. Every drug has its own FDA or EMA guidance. Look for "partial AUC" or "pAUC" in the pharmacokinetic section.

- Define the time window using reference data. Don’t guess. Use the Tmax or Cmax profile from the brand-name product’s clinical study reports.

- Use validated software. Phoenix WinNonlin, NONMEM, or R packages like PKPDsim are standard. Excel won’t cut it.

- Plan for larger sample sizes. Expect to increase your N by 25-40% compared to traditional studies.

- Consult a biostatistician early. Don’t wait until the study is designed. pAUC affects everything: dosing schedule, sampling timepoints, statistical power.

There’s no shortcut. But the payoff is clear: safer generics, fewer recalls, and better patient outcomes. The old way of saying "same total dose, same effect" is over. The future belongs to those who measure what matters-when it matters.

Henry Sy, January 15, 2026

lol so now we need a PhD just to make a generic pill? next they'll be asking us to calculate the emotional AUC of the patient before prescribing. i swear if i have to take a pill that took 3 months and $500k to approve, i'm just gonna eat an apple.

Jason Yan, January 15, 2026

Honestly, this is one of those rare cases where the science actually makes sense. We've been treating drug absorption like it's a bathtub filling up - total volume matters, right? But the body isn't a tub, it's a symphony. The first few minutes? That's the crescendo. If the violin comes in late or too loud, the whole piece falls apart. pAUC is like tuning the orchestra instead of just counting how many notes were played. It’s not about being fancy - it’s about not killing people because we were too lazy to look at the right part of the curve.

shiv singh, January 16, 2026

This is why america is dying. You people turn everything into a fucking math problem. Back in my day, if the pill looked the same and had the same ingredients, you took it. Now we need 50 subjects, special software, and a statistician with a caffeine IV just to make sure the drug doesn't make you feel "a little off" for 20 minutes. This isn't medicine. This is corporate theater. And the patients? They're the ones paying for it.

Robert Way, January 17, 2026

i think u mean PAUC not pAUC? or is it PauC? i keep seein it diff ways. also why do u need to ln transform? isnt that just for when data is skewed? and why cant we just use the same window for all drugs? like 0-2hrs? why so complicated??

Vicky Zhang, January 18, 2026

I just want to say thank you to everyone who’s pushing for this. I have a cousin who was on a generic opioid and kept having panic attacks right after taking it - like, 15 minutes in. The doctors thought it was anxiety. Turns out the generic spiked too fast. They switched him back to brand, and he cried because he felt normal again for the first time in months. If this saves even one person from that kind of terror, it’s worth every extra dollar and every extra subject.

Dylan Livingston, January 19, 2026

Oh wow. So the FDA, after decades of letting generics flood the market with zero oversight, suddenly discovered that people might not die if we actually measured the right thing? How novel. I’m sure the pharmaceutical CEOs are weeping into their champagne flutes over this "groundbreaking" innovation. Meanwhile, the 18-year-old in Ohio who got addicted to the "same" generic because it released too fast? Too bad. At least the company saved $350k. The real tragedy? We’re only doing this now because the lawsuits started piling up.

Andrew Freeman, January 20, 2026

pAUC is just a fancy way to say "we dont trust the generic makers" and honestly? fair. but the real issue is no one agrees on the time window. one guid says 0-1hr another says 0-2hr another says "till peak" - so if you’re a small company you just pick one and pray. its like playing russian roulette with your entire budget. also why do we need 50 subjects? i did a study with 24 and it was fine. they just wanted the numbers to look pretty.

says haze, January 21, 2026

The real irony here is that pAUC is a brilliant method - scientifically rigorous, clinically relevant, and statistically sound - yet its adoption is being sabotaged by the very institutions meant to promote it. The FDA’s product-specific guidances are a patchwork of contradictions, written by bureaucrats who don’t understand PK, reviewed by lawyers who don’t understand statistics, and enforced by compliance officers who don’t understand context. We’ve turned a tool for patient safety into a regulatory minefield. The solution isn’t more complexity - it’s standardization. But standardization requires leadership. And leadership, as always, is in short supply.