When a drug is designed to release slowly over time-like a pill that lasts 12 or 24 hours-it’s not just about convenience. It’s about safety, effectiveness, and making sure the medicine works the same way every time. That’s where modified-release formulations come in. These aren’t your standard pills. They’re engineered to control how and when the drug enters your bloodstream. But here’s the catch: just because two pills look the same doesn’t mean they work the same. And when it comes to generics, regulators demand proof that they’re truly equivalent. That proof? Bioequivalence studies. And for modified-release (MR) drugs, those studies are far more complex than for regular pills.

Why Modified-Release Drugs Need Special Rules

Immediate-release drugs hit your system fast and drop off quickly. Modified-release ones are built to avoid those spikes and crashes. Think of it like filling a bathtub with a slow drip instead of dumping a bucket in. The goal? Keep drug levels steady. That’s critical for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like warfarin, lithium, or certain seizure meds-where even a small change can mean the difference between control and danger. Studies show MR formulations reduce peak-to-trough fluctuations by 30-50% compared to immediate-release versions. They also cut dosing frequency. About 65% of MR drugs are designed for once-daily use, which boosts patient adherence by 20-30%. But for a generic version to be approved, it must prove it does all this just as well as the brand-name drug. That’s not something you can guess. It has to be measured, down to the hour.What Bioequivalence Really Means for MR Drugs

For regular pills, bioequivalence is usually about two numbers: AUC (how much drug gets absorbed over time) and Cmax (how high the peak concentration goes). If both fall within 80-125% of the brand drug, you’re good. But for MR drugs, that’s not enough. Why? Because a drug that releases in two phases-say, an immediate burst followed by a slow trickle-needs to match both parts. Missing one means the patient could get too much too soon, or too little later on. That’s why regulators now require partial AUC (pAUC) measurements. For example, with Ambien CR (zolpidem extended-release), the FDA demands two separate AUCs: one from time zero to 1.5 hours (the quick-release part) and another from 1.5 hours to infinity (the slow-release part). Both must fall within the 80-125% range. The same applies to drugs like Concerta (methylphenidate ER). In 2012, a generic version was rejected because it didn’t match the brand’s early release profile. Patients got less drug in the first two hours-enough to cause breakthrough symptoms.How Dissolution Testing Works (And Why It Matters)

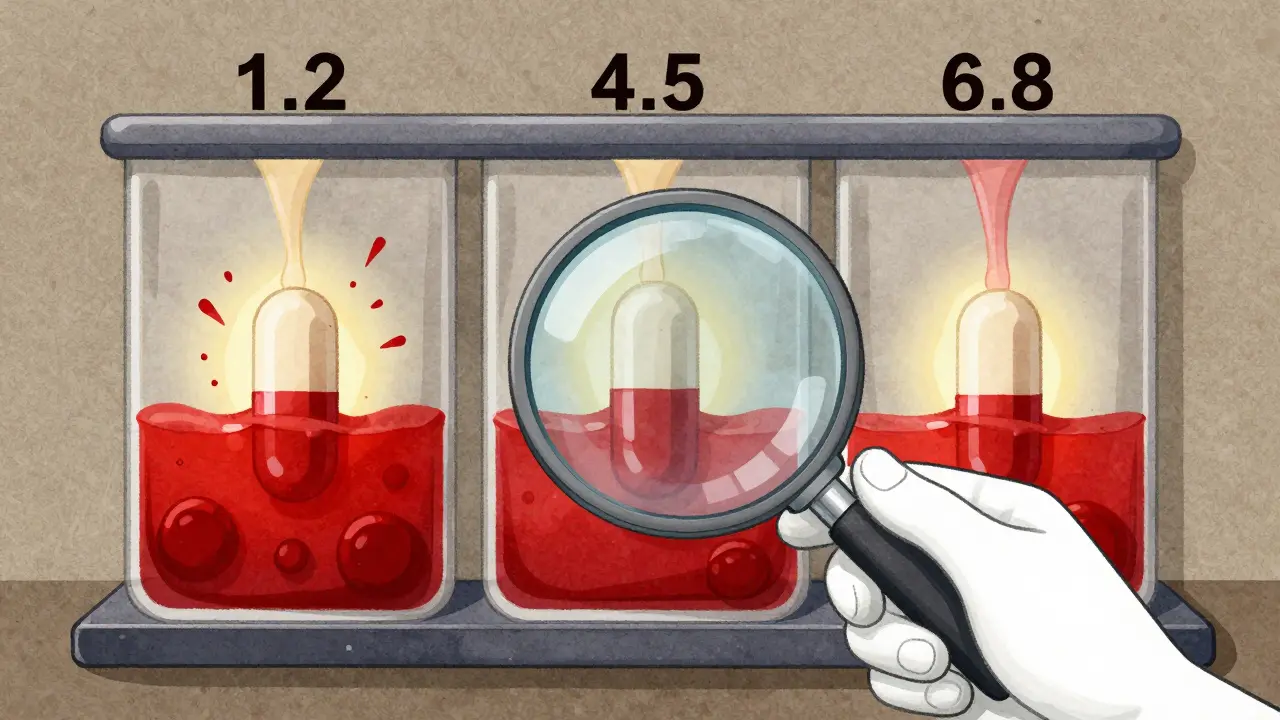

Before you even test on people, you test the pill in a lab. Dissolution testing simulates how the drug breaks down in the body. For MR tablets, the FDA requires testing at three pH levels: 1.2 (stomach), 4.5 (upper intestine), and 6.8 (lower intestine). Why? Because different parts of the gut have different acidity, and MR coatings are designed to respond to that. If a generic tablet dissolves too fast in stomach acid, it could dump the whole dose early-called “dose dumping.” The test uses a similarity factor called f2. If the test and reference products have an f2 value of 50 or higher, they’re considered similar enough to skip human studies in some cases. But here’s the kicker: for beaded capsules, you only need to test at one pH. For tablets, you need three. That’s a major difference-and a common failure point. One formulation scientist at Teva reported 35-40% of early ER oxycodone generics failed dissolution testing because they couldn’t match the pH profiles across all three conditions.Alcohol Isn’t Just a Party Drink-It’s a Risk Factor

Here’s something many patients don’t know: drinking alcohol with certain extended-release pills can be dangerous. Alcohol changes how the stomach and gut absorb the drug. For MR products with 250 mg or more of active ingredient, the FDA now requires alcohol interaction testing. You have to show the drug doesn’t suddenly release all its contents when exposed to 40% ethanol. Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER products were pulled from the market because of alcohol-induced dose dumping. One was an opioid painkiller-patients got a dangerous overdose after a single drink. This isn’t theoretical. It’s a real-world safety requirement. If you’re developing a generic ER drug, you must test it with alcohol. Skip it, and your application gets rejected.

Regulatory Differences Between FDA and EMA

The FDA and EMA don’t always agree. The FDA says single-dose studies are the gold standard for MR bioequivalence. They’re more sensitive to differences in drug release. The EMA, however, still requires steady-state studies in some cases-especially if the drug builds up in the body over time. That means patients take the drug daily for a week or more before blood samples are taken. Why the difference? The EMA argues that steady-state better reflects real-world use. The FDA says it adds unnecessary complexity and doesn’t improve accuracy. A 2018 paper by Dr. Lawrence Lesko called the EMA’s steady-state requirement “lacking scientific justification for most products.” But until the EMA changes its stance, companies developing global generics have to run both types of studies-doubling cost and time.What Happens With Highly Variable Drugs?

Some drugs vary wildly from person to person. Warfarin, for example, can have a within-subject coefficient of variation over 30%. For these, standard 80-125% bioequivalence rules don’t work. Too wide a range means you could approve a generic that’s too weak or too strong for some patients. That’s where Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE) comes in. It lets the acceptance range widen based on how variable the reference drug is. But there’s a cap: the upper limit can’t exceed 57.38% of the reference’s variability. RSABE adds 6-8 months to development timelines. It requires advanced statistical modeling and more participants. One Mylan pharmacologist noted that RSABE for MR drugs is “the most complex part of our approval process.”Costs and Challenges in Developing MR Generics

Developing a generic MR drug isn’t just harder-it’s way more expensive. On average, it costs $5-7 million more than a regular immediate-release generic. Why? Because of the extra studies: dissolution at multiple pH levels, alcohol testing, pAUC analysis, RSABE modeling, and sometimes multiple-dose or steady-state trials. A single-dose MR bioequivalence study runs $1.2-1.8 million. An IR study? $0.8-1.2 million. And failure rates are high. Between 2018 and 2021, 22% of MR generic applications were rejected for inadequate pAUC data. Another 45% failed formulation proportionality testing-meaning they couldn’t prove their 10mg, 20mg, and 40mg versions released drug the same way. The good news? Some companies have cracked the code. Sandoz got approval for an ER tacrolimus generic by matching dissolution profiles so closely (f2=68 at pH 6.8) that they skipped human studies entirely-saving $1.5 million and 10 months.

What You Need to Get Started

If you’re entering this space, you need more than a lab. You need expertise in:- Dissolution method development (USP Apparatus 3 or 4, not just Apparatus 2)

- Pharmacokinetic modeling (using tools like Phoenix WinNonlin or NONMEM)

- Statistical analysis of RSABE data

- Understanding product-specific guidances (PSGs)-there are over 150 for MR drugs

Josh Potter, December 16, 2025

Bro, I just read this and my brain exploded. Who the hell thought up all these pH levels and f2 factors? It’s like they’re trying to make generics illegal on purpose. I got a prescription for ER oxycodone last year and my pharmacy switched brands-no one told me the new one might dump all the drug if I had a beer. That’s wild.

And don’t even get me started on the alcohol testing. I’ve seen people chug whiskey with their Adderall XR. They think it’s ‘enhancing’ it. Nah, bro. They’re just one sip away from an ER trip. This shit’s real.

Anna Giakoumakatou, December 16, 2025

Oh, so now we’re treating pharmaceuticals like fine wine? ‘Ah yes, the 2021 Concerta vintage-notes of delayed release with a subtle hint of regulatory noncompliance.’ How quaint. I suppose the FDA’s 117-page manifesto on extended-release bioequivalence is the new ‘Moby Dick’ for pharmacists who’ve never seen a sunset.

Meanwhile, actual patients are just trying to survive their depression without having to memorize dissolution profiles. But sure, let’s keep the ivory tower intact. The masses can’t possibly understand that a 0.2-hour delay in absorption might be ‘therapeutically significant.’

Martin Spedding, December 17, 2025

35% of ER oxycodone generics failed dissolution? No shocker. Most of these labs are run by interns who think ‘pH 6.8’ is a new energy drink. And don’t even mention RSABE-half the time the stats are just made up with Excel macros.

Also, why does the EMA still do steady-state? That’s like requiring you to run a marathon before you can prove you can walk. Waste of time. Waste of money. Waste of patients’ lives.

Donna Packard, December 17, 2025

This is actually really important info, and I’m glad someone laid it out so clearly. I work in a clinic and see patients struggle with adherence all the time. If we can make generics that truly match the brand’s release profile, it’s a win for everyone.

Especially for the elderly who are on 8+ meds. One less pill a day, and they’re more likely to take it right. That’s not just science-it’s care.

Patrick A. Ck. Trip, December 18, 2025

It is imperative to recognize that the regulatory frameworks governing modified-release formulations are grounded in empirical evidence derived from clinical outcomes and pharmacokinetic modeling. The introduction of partial AUC metrics and f2 similarity factors represents a significant advancement in ensuring therapeutic equivalence.

While cost and complexity are undeniable challenges, the alternative-suboptimal bioequivalence-poses a far greater risk to public health. The FDA’s guidance, though dense, is methodologically rigorous and should be regarded as the gold standard.

Sam Clark, December 19, 2025

One thing I’ve learned from working with generic manufacturers is that the real heroes are the formulation scientists who spend years tweaking coatings and bead sizes just to hit that f2=50 threshold.

They’re not in it for fame. They’re in it because they know someone’s life depends on that pill releasing the right amount at the right time. We should treat them like the engineers they are.

amanda s, December 21, 2025

Why does the EMA even exist? America invented modern medicine. We don’t need some European bureaucrat telling us how to test pills. If the FDA says single-dose is enough, that’s it. End of story. This is why we’re #1 in pharma innovation-because we don’t waste time with pointless double-testing.

And if you can’t pass our standards, then you don’t get into our market. Simple. No excuses.

Peter Ronai, December 21, 2025

You think this is bad? Wait till you hear about the 2023 case where a generic lithium ER got approved because the lab used the wrong dissolution apparatus. Patient had a seizure. Got sued. Company went bankrupt.

And now? The FDA is letting some companies skip human trials using ‘IVIVC models’-which are basically fancy computer simulations. You can’t trust math over meat. We’re talking about people’s brains here. Not Excel sheets.

Michael Whitaker, December 23, 2025

It’s fascinating how the FDA’s guidance document is rated higher than the EMA’s-8.2 vs 6.8-despite the fact that both are essentially unreadable to anyone without a PhD in pharmaceutics. The real issue isn’t which agency is better. It’s that the entire system has become a black box.

Patients don’t care about pAUC or f2. They just want their meds to work. And if they can’t even understand the paperwork behind their prescription, how is that ethical?

Jigar shah, December 25, 2025

Very detailed and well-structured. I’m from India and we’re just starting to build capacity in this area. The mention of USP Apparatus 3 and 4 is critical-most labs here still use Apparatus 2 out of convenience. This post should be mandatory reading for our regulatory trainees.

Also, the RSABE section was eye-opening. We assumed widening the range was just a loophole. Turns out it’s a scientifically grounded safety net. Thank you.

Joe Bartlett, December 25, 2025

Dude, I just saw a guy on TikTok say he crushes his ER meds for a faster high. This post is literally saving lives.