When a drug’s patent runs out, prices don’t just dip-they collapse. It’s not a slow fade. It’s a crash. And it’s not just a theory. It’s happening right now, with real people paying $10 instead of $850 for the same pill. The moment a brand-name drug loses patent protection, the market flips from a monopoly to a free-for-all. And that’s when the real savings begin.

What Happens the Day After Patent Expires?

The first generic version hits shelves within months, often priced 20% to 30% lower than the brand. That’s the baseline. But here’s the catch: the real price drop doesn’t come from the first generic. It comes from the third, fifth, or tenth. Each new manufacturer brings more competition. More competition means more pressure to cut prices. By the time five or six generics are on the market, the drug can be selling for less than 10% of its original cost. Take Eliquis (apixaban), a blood thinner. Before its patent expired in 2020, patients paid around $850 a month. Within a year, generic versions hit the market. By 2023, the same dose cost $10 a month. That’s not a typo. That’s 98% off. And it’s not rare. According to a 2023 study in JAMA Health Forum, U.S. drug prices fell 82% over eight years after patent expiry. The first generic cut prices by 15-20%. The tenth? It drove them down 80-90%.Why Do Prices Drop So Fast?

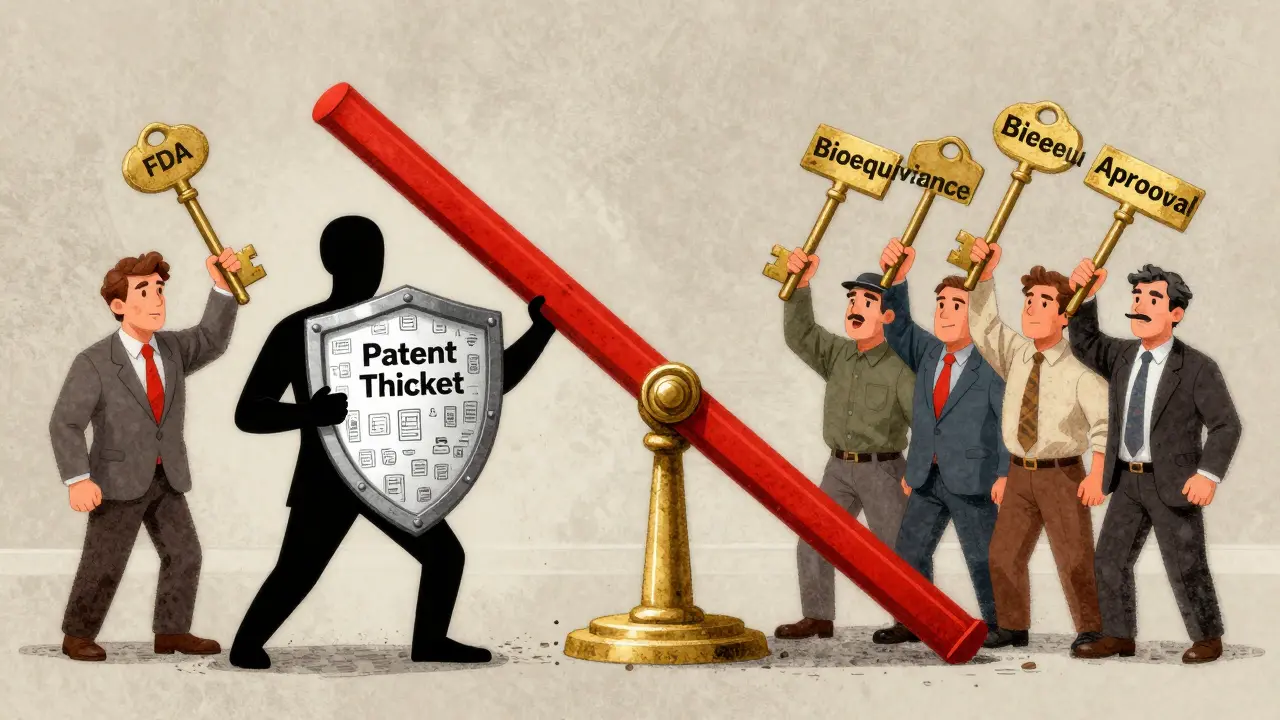

It’s simple economics: supply meets demand. When only one company makes a drug, they set the price. No competition. No pressure. But as soon as others can legally copy it, they do. And they don’t need to spend millions on research. They just need to prove their version works the same way. That’s called bioequivalence. It’s cheaper, faster, and the FDA approves it in about 10 months for simple pills. Manufacturers of generics don’t need fancy marketing teams. They don’t need to pay for TV ads or celebrity endorsements. Their only goal is to sell as much as possible at the lowest price. So they undercut each other. And the customer wins. But it’s not just about pills. Complex drugs like biologics-injectables used for arthritis, cancer, and autoimmune diseases-take longer. These aren’t simple chemicals. They’re made from living cells. Copying them is harder. That’s why biosimilars (the generic version of biologics) take years to enter the market. Humira, a top-selling arthritis drug, had its first biosimilar approved in 2023-seven years after its main patent expired. Why? Because AbbVie filed over 130 secondary patents to delay competition. That’s called a patent thicket. And it’s common.Patent Thickets: The Hidden Delay

Most people think patent expiration means instant competition. It doesn’t. Drug companies have mastered a tactic called “evergreening.” They take an existing drug, make a tiny change-a new dosage form, a slightly different chemical tweak, a new delivery method-and file a new patent. This isn’t innovation. It’s legal maneuvering. According to the R Street Institute, 78% of new patents filed between 2010 and 2023 weren’t for new drugs. They were for old ones. And 70% of the top 100 prescribed drugs had their exclusivity extended at least once. The average blockbuster drug now gets 10 to 15 secondary patents. Together, they add 12 to 14 extra years of monopoly pricing. Semaglutide (Ozempic, Wegovy) is a current example. The base compound patent expires in 2026. But the manufacturer has filed 142 patents across three formulations. Experts say this could delay generic entry until 2036. That’s a decade of inflated prices, even after the original patent is gone.

Why Do Prices Vary So Much by Country?

The U.S. isn’t the only country dealing with this. But it’s the worst. After eight years, U.S. drug prices fell 82%. In the UK, they fell 60%. In Australia, 64%. In Switzerland? Just 18%. Why? Because other countries control prices. Germany, France, and Canada use reference pricing-they look at what other countries pay and set their own prices accordingly. They negotiate directly with drugmakers. The U.S. doesn’t. Medicare can’t negotiate prices for most drugs. Insurance companies do, but they often prioritize rebates over list price. That means even when generics are available, patients might not see the savings if their plan doesn’t put the cheaper version on its preferred list. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 68% of insured adults saved money when generics came out. But 22% said their insurance made them wait-sometimes for months-before covering the cheaper version. That’s because rebates between drugmakers and insurers can make the expensive brand more profitable for the plan than the generic.Who Benefits the Most?

Patients. Healthcare systems. Taxpayers. Everyone except the original drugmaker. In 2023, the U.S. spent $400 billion on prescription drugs. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that generic and biosimilar competition will save $1.7 trillion over the next decade. That’s money that can go to hospitals, doctors, or lower premiums. But it’s not automatic. If patent thickets aren’t cracked, those savings get delayed-on average, by 4.2 years per drug. Generic manufacturers are thriving. The global market was worth $407.5 billion in 2023 and is projected to hit $700 billion by 2030. Companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz are investing billions to build factories, hire chemists, and file applications. They’re betting on patent cliffs. And they’re winning.

Jay Amparo, January 11, 2026

Just saw my neighbor fill her Eliquis script for $12 cash. Same pill. Same dose. Used to cost her $800 a month. I cried. Not because I’m emotional, but because this is what justice looks like in a broken system.

Generic manufacturers aren’t villains. They’re the quiet heroes who turned a monopoly into a marketplace. And yeah, the pharma execs are pissed. Good.

India’s generic makers? Absolute legends. They’re the reason millions of Americans aren’t choosing between insulin and rent.

I’m not saying it’s perfect. Patent thickets are a scam. But when the system finally breaks open? It’s beautiful.

Let’s not forget: every time a biosimilar enters, someone’s child gets to see their parent walk again. That’s not economics. That’s humanity.

And honestly? If you’re still paying brand price when a generic exists, you’re either not asking or you’re being screwed by your insurer. Both are fixable.

Pharma didn’t invent medicine. They just learned how to monetize it. We’re just learning how to take it back.

Lisa Cozad, January 11, 2026

My dad’s on Humira. We waited 7 years for a biosimilar. When Amjevita finally came out, his copay dropped from $120 to $15. We didn’t celebrate with champagne-we just sat there in silence, realizing we’d been overpaying for years.

Insurance didn’t switch him automatically. We had to fight. Literally. Called three times. Filed a prior auth. Got a letter from the pharmacy saying ‘the brand is preferred.’

Turns out, the rebate on the expensive version was bigger for the plan. So they kept pushing it. Even though it cost us more.

This isn’t just about patents. It’s about who controls the system. And right now, it’s not the patient.

Saumya Roy Chaudhuri, January 12, 2026

Ugh, you people are so naive. The U.S. pays more because we fund global R&D. If we didn’t, there’d be no new drugs at all. India and China just copy and profit. They don’t pay the $2.6 billion to develop a drug.

And biosimilars? They’re not identical. The FDA says so. Minor differences in glycosylation can cause immune reactions. You think your grandma’s arthritis is worth risking anaphylaxis for $10 savings?

Also, 78% of patents are for old drugs? So what? Innovation isn’t just about new molecules. Delivery systems, combo therapies, extended release-those matter too.

And don’t get me started on the ‘patent thicket’ narrative. That’s just anti-pharma propaganda from people who don’t understand IP law.

Also, if you’re paying cash for generics, you’re not even using insurance. That’s not a win-it’s a workaround for a broken system you helped create by voting for deregulation.

Ian Cheung, January 12, 2026

Patent expiration is the only time pharma gets slapped with reality

They spend billions on ads telling you your life depends on their $1000 pill

Then the generic hits and suddenly your doctor’s like ‘oh yeah this one works too’

And you realize the pill didn’t change

Just the price tag

And the people who made the original? They’re already on their third yacht

Meanwhile your neighbor’s kid is on a generic version of Ozempic

And it’s saving their life

And they didn’t need to take out a loan

That’s not capitalism

That’s just common sense

And yeah I know the ‘but innovation’ argument

But if you’re still patenting the same molecule with a new color capsule in 2025

You’re not innovating

You’re just playing Monopoly with people’s health

anthony martinez, January 13, 2026

So let me get this straight. The system is rigged, but the solution is to let generic companies undercut each other until the original maker goes bankrupt? And we’re supposed to cheer?

Meanwhile the same companies that made $20B off Humira are now lobbying to block biosimilars in Europe. And we’re acting like this is a victory?

It’s not. It’s just the next phase of the same game.

Patent expiration doesn’t fix anything. It just shifts the profit margin.

And the FDA approves generics in 10 months? Sure. But only if you don’t have a 142-patent thicket holding them up.

So what’s the real solution?

Not generics.

Price controls.

But that’s too scary for this country to even say out loud.

Mario Bros, January 15, 2026

Yo if you’re still paying full price for a drug with a generic version-stop.

Go to GoodRx. Type in the name. See the cash price.

90% off? Yeah. Happens every day.

My cousin was on a $700/month asthma inhaler. Generic? $12.

She didn’t even know it existed until her pharmacist said ‘hey, you know you can get this for less than your coffee?’

Don’t wait for your insurance to ‘catch up.’

Be the person who asks.

Be the person who says ‘nope, I’m not paying that.’

You’re not being difficult.

You’re being smart.

And you’re not alone.

- your pharmacy buddy 🙌

Jake Nunez, January 15, 2026

India’s generic industry isn’t just cheap-it’s a global public health engine. They make 40% of all generics consumed in the U.S. and 80% of those used in Africa.

And they do it without subsidies. No tax breaks. No government funding. Just brilliant chemists, low labor costs, and a culture that sees medicine as a right, not a profit center.

Compare that to the U.S., where we spend $100 billion a year on direct-to-consumer ads for drugs that cost 10x more than identical versions abroad.

It’s not that we’re sick.

It’s that we’ve been sold a myth.

And that myth is: innovation requires monopoly pricing.

But if India can make life-saving drugs at 5% of the cost, then the myth is dead.

And the real innovation? That’s happening in labs in Ahmedabad, not Manhattan.

Christine Milne, January 16, 2026

It is patently obvious that the erosion of intellectual property rights in the pharmaceutical sector constitutes a systemic threat to American scientific leadership.

The notion that generic manufacturers, operating under inferior regulatory standards and without the burden of clinical trial investment, are entitled to the same market access as innovators is not only economically unsound-it is morally reprehensible.

Furthermore, the comparison to India’s pharmaceutical sector is not a point of pride, but of national shame. Their model is predicated on intellectual theft, not innovation.

And to suggest that Medicare should negotiate prices is to invite price controls that will inevitably lead to drug shortages, reduced R&D, and the eventual collapse of the American biotech ecosystem.

One must ask: Would you rather have a $10 pill-or no pill at all, because the innovator went bankrupt?

Bradford Beardall, January 18, 2026

Wait-so if a drug’s patent expires and the price drops 90%, does that mean the original company was overcharging by 90% the whole time?

And if so… why didn’t anyone notice?

And if they did notice… why didn’t they do anything?

Is it because the system is designed to make patients feel like they’re getting ‘value’ from a $800 pill when the pill is literally identical to the $10 one?

And if the FDA says they’re bioequivalent… then why does the brand name still have marketing teams?

And why do doctors still write the brand first?

And why do insurance plans still push the expensive version?

Is this just a giant, slow-motion scam?

Because if it is… we’re all complicit.

McCarthy Halverson, January 18, 2026

Check your pharmacy. Ask for generic. Pay cash if insurance won’t cover it. Done.

Biologics? Ask for biosimilar. Same thing.

Don’t wait for the system to fix itself.

Fix it yourself.

It’s not hard.

It’s just inconvenient.

And that’s the whole point.

Michael Marchio, January 19, 2026

Let’s be honest here. The entire pharmaceutical industry is built on a Ponzi scheme disguised as innovation. They spend $2.6 billion to develop a drug, sure. But then they spend $5 billion marketing it. And then they spend $1 billion on lawyers to extend patents with meaningless tweaks. And then they charge $1000 a pill because they know you’ll pay it.

And then when the patent expires? They just launch a new version of the same drug with a new name and a new patent. And the cycle continues.

And we’re supposed to be impressed by the ‘efficiency’ of generics?

That’s like being impressed that the thief returned your wallet after stealing it for ten years.

The real crime isn’t the patent expiration.

The real crime is that we ever let them get away with it in the first place.

And now we’re patting ourselves on the back because we finally got the $10 pill?

What kind of society celebrates the bare minimum?

We should be ashamed.

Not grateful.

Jake Kelly, January 21, 2026

Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. I’ve been on a brand-name drug for three years. Last month I switched to the generic. Saved $700 a month.

My anxiety didn’t get worse. My symptoms didn’t come back.

It’s the same pill.

And I feel stupid for not asking sooner.

So thank you for reminding me-and everyone else-that asking questions isn’t being difficult.

It’s being alive.