When you pick up a prescription for generic lisinopril or metformin, you probably assume the price is simple: manufacturer makes it cheap, pharmacy sells it cheap. But the real story happens behind the scenes-in warehouses, contracts, and pricing tables no one talks about. Generic drug wholesale isn’t just logistics. It’s a high-volume, low-margin game where a few big players make more profit per pill than the companies that make the drugs.

Who Controls the Flow of Generic Drugs?

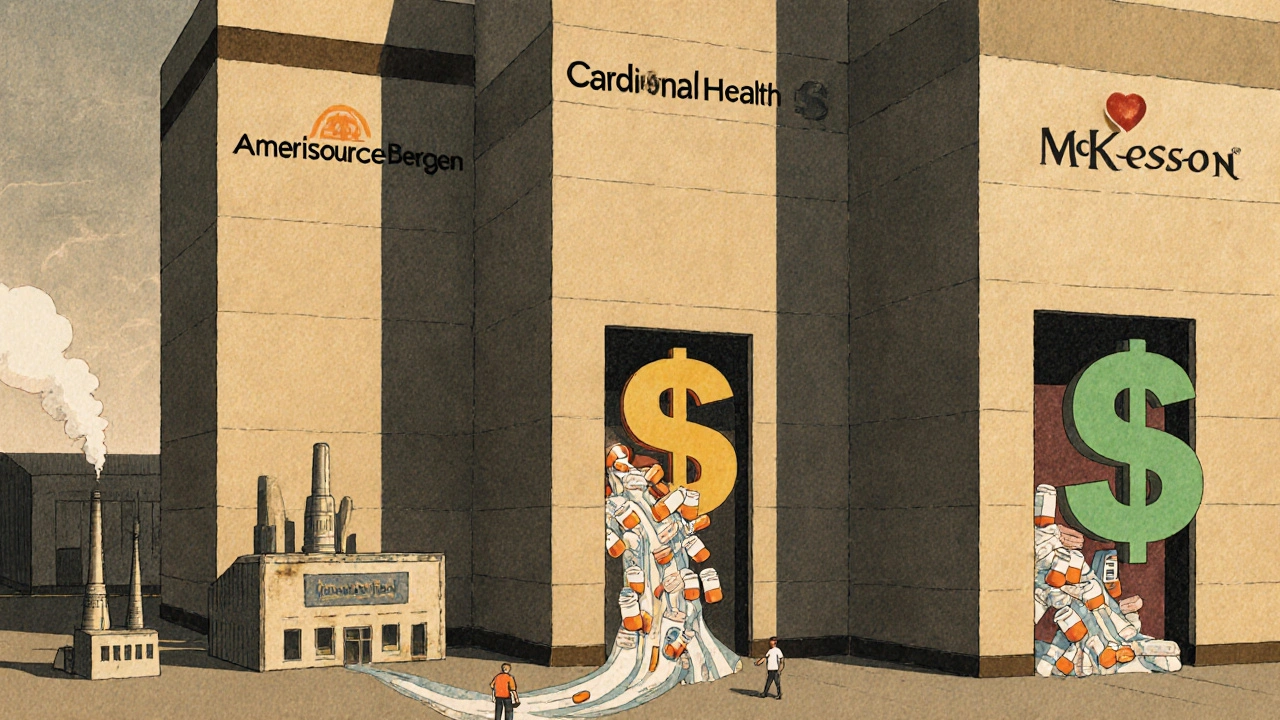

Three companies-AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson-move about 85% of all generic pharmaceuticals in the U.S. They’re not manufacturers. They don’t make the pills. They don’t prescribe them. But they control the pipeline from factory to pharmacy. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s the result of decades of consolidation, regulation, and economic incentives that favor big distributors. These wholesalers don’t just ship boxes. They negotiate prices with manufacturers, set minimum order sizes, manage inventory risk, and even influence which drugs get stocked-or delayed. In 2009, generics made up only 9% of the wholesalers’ total revenue. But they generated 56% of their gross profits. Why? Because the math works differently for generics.Why Generics Are a Goldmine for Wholesalers

Branded drugs are expensive. Manufacturers charge $100 for a pill, pharmacies mark it up to $120, and patients pay $150. Everyone makes money. But with generics? The story flips. Generic manufacturers sell their pills at rock-bottom prices-sometimes just pennies per unit. To win contracts, they slash prices even further. Wholesalers buy a bottle of 100 generic metformin tablets for $2. They sell it to a pharmacy for $3. The pharmacy sells it to you for $4. That’s a 50% markup from manufacturer to pharmacy. But here’s the catch: the wholesaler’s profit isn’t on the $1 difference. It’s on volume and efficiency. The USC Schaeffer Center found wholesalers make eleven times more profit per dollar spent on generics than on branded drugs. For every $1 spent on a branded drug, wholesalers make about $0.03 in profit. For every $1 spent on a generic, they make $0.32. That’s not a typo. It’s the result of what economists call “volume arbitrage.” Wholesalers buy in bulk-thousands of units at a time. They pay less per unit because of tiered pricing. If you order 100 units, you pay $1 per pill. Order 500? You pay $0.80. Order 1,000? $0.70. They stockpile. They move inventory fast. And because the cost to store and handle a generic pill is nearly the same as a branded one, their overhead doesn’t rise much. Profit per unit? Tiny. Profit per shipment? Massive.How Pricing Actually Works in Generic Wholesale

There are four main pricing models used in generic drug distribution:- Cost-plus pricing: Wholesalers add a fixed percentage (usually 20-50%) to their cost of goods. Simple, but risky if market prices drop.

- Market-based pricing: They match competitors’ prices. If McKesson drops the price on amoxicillin, Cardinal follows. This keeps margins thin but ensures volume.

- Value-based pricing: Rare in generics. Used mostly for specialty drugs or when a generic is in short supply.

- Tiered pricing: The real engine of profitability. Bulk discounts aren’t just incentives-they’re profit multipliers. A pharmacy buying 500 units of a generic at $0.70 per pill pays $350. If they bought 100 units at $1.00, it would cost $100. The wholesaler’s profit margin shrinks slightly, but they sell five times more units. And they’re not losing money-they’re banking on volume and speed.

The Inverted Profit Chain

Here’s the twist: the people who make the drugs make less money on generics than the people who move them. Branded drug manufacturers gross 76.3% profit per unit. Generic manufacturers? Only 49.8%. That’s still decent. But look at the distribution side. Pharmacies make 42.7% gross profit on generics. Wholesalers? Their net margin is only 0.5%. Sounds low, right? But because they move billions of units, that 0.5% adds up to billions in profit. In 2009, the Big Three made $1.7 billion more in gross profit from generics than from branded drugs-even though generics brought in far less revenue. It’s like selling rice. A farmer grows rice for $0.10 a pound. A grocery store sells it for $1. The wholesaler buys it for $0.20 and sells it for $0.50. The farmer makes $0.05 profit. The wholesaler makes $0.30. The store makes $0.50. But if the wholesaler sells 100 million pounds? They make $30 million. The farmer? $5 million. The store? $50 million. Everyone wins. But the middleman wins on scale.Why Shortages Change Everything

In 2020, the pandemic disrupted supply chains. Generic drug prices spiked. In 2021 and 2022, they dropped again-deflation kicked in. But in 2023, something changed. Shortages returned. When a generic drug like doxycycline or hydrochlorothiazide becomes scarce, wholesalers stop discounting. They stop competing on price. They hold inventory. And prices jump. Suddenly, a drug that cost $0.10 a pill sells for $0.80. Pharmacies scramble. Patients pay more. And wholesalers? Their profit per unit explodes. This isn’t price gouging. It’s market mechanics. The system is designed to reward scarcity. When supply drops, the few players with stock gain enormous leverage. The Commonwealth Fund calls this “strategic inventory hoarding.” It’s legal. It’s common. And it’s one reason why drug prices don’t always fall-even when competition increases.Who Wins? Who Loses?

Patients and small pharmacies lose. Big wholesalers win. Manufacturers? They’re stuck in the middle. Generic manufacturers are forced to compete on price. They can’t afford to build brand loyalty. They can’t charge more. So they cut costs. They move production overseas. They reduce quality control. And when a shortage hits, they’re slow to ramp up. Why? Because they’re not rewarded for reliability. They’re rewarded for lowest bid. Pharmacies, especially small ones, have no bargaining power. They buy from the same three wholesalers. If one raises prices, they have nowhere else to go. Independent pharmacies often pay more than hospital chains or big retail chains like CVS or Walmart. Patients? They’re the last in line. Even with insurance, copays for generics can spike overnight. A $4 prescription becomes $20 because a wholesaler decided to stop discounting a drug that’s suddenly in short supply.

What Could Change?

There are no easy fixes. But experts agree on two things: First, more competition. Right now, the Big Three have too much power. If smaller wholesalers could scale up-through better logistics, shared inventory systems, or government-backed distribution networks-prices could drop. Second, transparency. No one knows the real cost of a generic pill. Not even most pharmacists. If pricing were public-like how electricity or gas prices are posted-wholesalers couldn’t hide their margins. Patients and policymakers could see where the money goes. The USC Schaeffer Center put it simply: “Greater scrutiny of pricing policies and more competition throughout the distribution system is warranted.” It’s not about blaming wholesalers. It’s about fixing a system that rewards volume over fairness, and scarcity over stability.What You Can Do

If you’re a patient: Ask your pharmacist if there’s a different generic brand available. Sometimes, the same drug from a different manufacturer costs 30% less. It’s the same pill-just a different label. If you’re a small pharmacy owner: Join a buying group. Pool your orders with other independents. You’ll get tiered pricing you wouldn’t get alone. If you’re a policymaker: Look at the wholesale tiered pricing structure. Why do discounts kick in at 100 units? Why not 10? Why not 500? The thresholds aren’t random. They’re designed to lock in volume. That’s not efficiency. That’s control.Final Thought

Generic drugs are supposed to save money. And they do-when the system works. But when the middlemen control the flow, and profit from scarcity instead of scale, the savings disappear. The real cost of a generic pill isn’t in the factory. It’s in the warehouse. And until we see what’s happening behind those doors, we’re just guessing why prices go up.Why are generic drugs sometimes more expensive than brand-name drugs?

They’re not usually more expensive-but they can be, temporarily. When a generic drug has a shortage, wholesalers stop offering bulk discounts. Pharmacies pay more per unit, and those costs get passed to patients. Meanwhile, the brand-name version may still be discounted by the manufacturer to retain market share. So in rare cases, the generic ends up costing more than the brand-temporarily.

Do wholesalers cause drug shortages?

They don’t cause shortages directly, but they can worsen them. Wholesalers often prioritize high-margin drugs or those with steady demand. If a generic drug has low profit margins or is hard to store, they may reduce orders. That signals manufacturers to cut production. Over time, that leads to actual shortages. It’s a ripple effect, not a conspiracy.

Why don’t pharmacies just buy directly from manufacturers?

Most manufacturers won’t sell to individual pharmacies. They require minimum order volumes-often thousands of units-that small pharmacies can’t meet. Wholesalers act as aggregators, combining orders from hundreds of pharmacies into one large shipment. It’s logistics, not greed.

Are generic drug prices regulated by the government?

No. Unlike insulin or some Medicare-covered drugs, most generics aren’t price-controlled. Wholesalers and pharmacies set their own prices. The only exception is Medicaid, which has a maximum allowable cost for certain generics. For everyone else, it’s a free market-no matter how concentrated that market is.

How do PBMs (pharmacy benefit managers) fit into this?

PBMs negotiate rebates with manufacturers and set formularies-lists of approved drugs. They often push pharmacies to use certain generics because they get a cut of the savings. But they don’t control wholesale pricing. That’s still up to the three big distributors. PBMs influence which drugs are prescribed, but wholesalers control how much they cost to buy.

Is there a difference between generic drug wholesalers in the U.S. and other countries?

Yes. In countries like the UK, Canada, or Germany, governments set or cap wholesale prices. Wholesalers are paid a fixed fee to distribute, not a percentage of the drug’s price. That’s why generic drugs are often cheaper overseas. The U.S. system is unique in letting distributors profit from volume and scarcity without price caps.

Nicole Ziegler, November 21, 2025

lol at how we think generics are cheap 🤡💸

Bharat Alasandi, November 21, 2025

this is why i always ask my pharmacist for the cheapest generic brand. same pill, sometimes 30% less. no one tells you this. 🤫

Ravi boy, November 21, 2025

in india we get generics for like 5 rupees but here in us its wild how the middlemen eat the whole pie

Matthew Karrs, November 22, 2025

this is all part of the pharmaceutical industrial complex. they want you sick. they want you dependent. they want you paying $20 for a pill that costs 2 cents to make. wake up sheeple.

Matthew Peters, November 23, 2025

the volume arbitrage thing is so real. i used to work in logistics for a regional distributor. we moved like 2 million units of metformin a month. profit per unit was a penny. but multiply that by 2 million? we were basically printing money. it’s not about the markup-it’s about the volume.

Aruna Urban Planner, November 24, 2025

the structural imbalance here is fascinating. it’s not greed-it’s systemic. the incentives are misaligned. manufacturers compete on price, distributors on scale, pharmacies on convenience. no one is incentivized to stabilize supply. it’s a tragedy of the commons wrapped in a pill bottle.

Kristi Bennardo, November 25, 2025

This is an outrage. A national disgrace. The fact that three corporations control 85% of the generic supply chain while patients are left paying exorbitant prices for life-saving medication is not just unethical-it’s criminal. Where are the regulators? Where is Congress? This isn’t capitalism-it’s corporate feudalism.

Shiv Karan Singh, November 27, 2025

lol you think this is bad? wait till you find out the FDA approves generics from factories that don't even have running water. and you still take it? you're a dumbass. #genericlife

Liam Strachan, November 28, 2025

Interesting breakdown. Reminds me of how milk distribution works in the UK-fixed fees, no volume games. Makes you wonder if we’re overcomplicating things here. Maybe we just need to cap distributor margins?

Michael Fessler, November 29, 2025

one thing people miss: wholesalers absorb returns. if a pharmacy gets a bad batch, they send it back. that’s a cost. also, they handle inventory risk. if demand drops, they’re stuck with it. so yeah, margins are thin-but the risk is real. still, the profit skew is wild.

Nosipho Mbambo, November 29, 2025

This is why I don't trust the American healthcare system. It's a scam. A multi-billion dollar pyramid scheme. And we're all just the suckers at the bottom. The fact that people think this is normal is terrifying.

Gerald Cheruiyot, November 30, 2025

i think the real problem isn’t the wholesalers-it’s the lack of transparency. if every price change was public, like a stock ticker, we’d see the manipulation in real time. imagine if you could see the wholesale price of lisinopril drop when a new manufacturer enters the market. that’d force competition. but nope. it’s all hidden behind NDAs and proprietary pricing models.

Alyssa Torres, December 2, 2025

i used to work at a small independent pharmacy. we paid 20% more than CVS because we couldn’t hit the 500-unit threshold. we’d order 200, get charged $1.00 per pill. CVS ordered 5,000, paid $0.70. then they sold it for $4. We sold it for $5. And we were the ones getting called ‘price gougers.’ it’s rigged.

Summer Joy, December 3, 2025

this is why i stopped taking generics. i switched to brand-name. at least i know who’s making it. and yeah, it’s more expensive-but i’m not gambling on whether my blood pressure med came from a factory with no quality control. #safetyoverprice

daniel lopez, December 4, 2025

you think this is bad? wait till you find out the same wholesalers also own PBMs. they’re not just moving the pills-they’re deciding which ones get covered. they’re not middlemen. they’re the whole damn system. and they’re all connected. it’s a monopoly. it’s a cartel. it’s a crime.