When a generic drug company wants to prove its product works just like the brand-name version, it doesn’t test it on thousands of people. It uses a smarter, leaner method: the crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick-it’s the backbone of how regulators like the FDA and EMA decide whether a generic drug can be sold. And it’s why you can buy a $5 version of a $50 pill and know it’ll do the same job.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence Studies

Imagine you’re testing two different painkillers. In a normal study, you’d split people into two groups: one gets Drug A, the other gets Drug B. But people are different. One group might be older, heavier, or metabolize drugs slower. That noise hides the real difference between the drugs. Crossover design fixes that. Every participant gets both drugs-just not at the same time. First, they take Drug A. After a break, they take Drug B. Because each person is their own control, you remove the noise of individual differences. That means you need far fewer people to get clear results. For bioequivalence studies, this isn’t just helpful-it’s mandatory. The FDA and EMA both say crossover designs are the gold standard. Why? Because they cut sample sizes by up to 80%. A study that would need 72 people in a parallel design might only need 24 in a crossover. That saves time, money, and reduces burden on volunteers.The Standard 2×2 Crossover: AB/BA

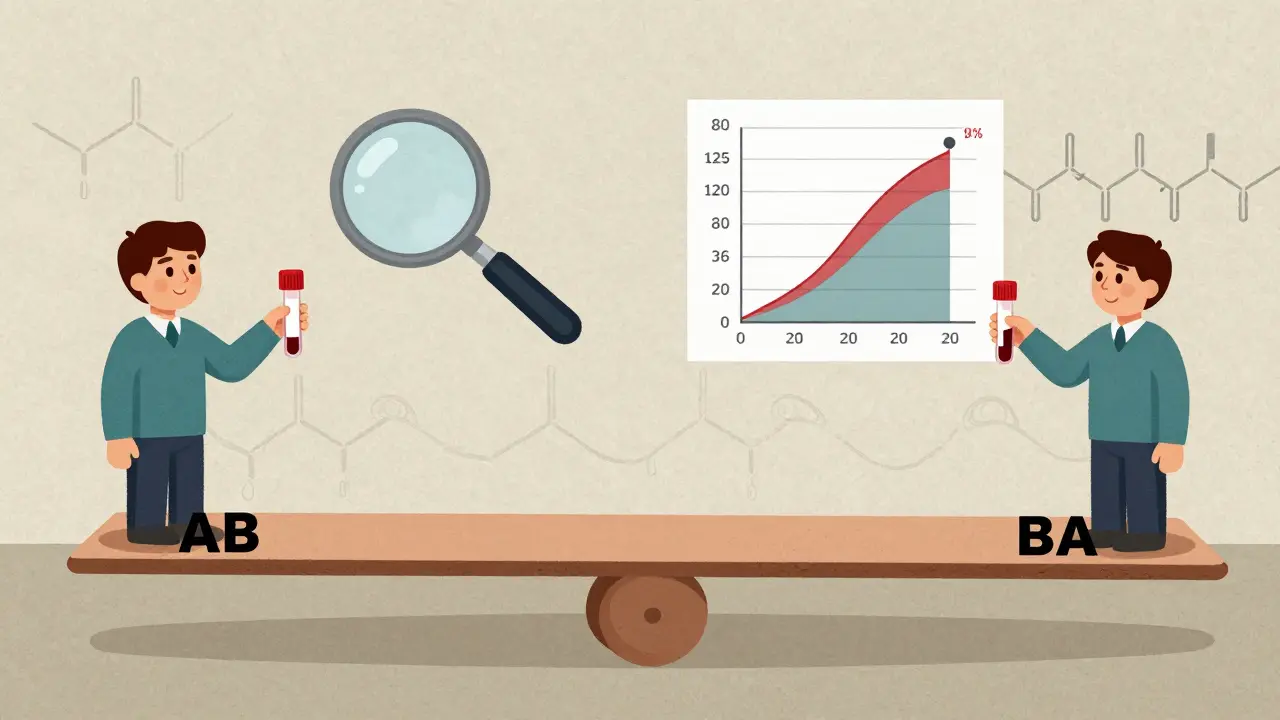

The most common setup is the 2×2 crossover: two periods, two sequences. Half the participants get the test drug first, then the reference (AB). The other half get the reference first, then the test (BA). This balancing prevents period effects from skewing results. Between each dose, there’s a washout period. This isn’t just a waiting room-it’s critical. The washout must last at least five half-lives of the drug. That’s the time it takes for the body to clear over 97% of the substance. If you skip this, leftover drug from the first period can mess up the second. That’s called carryover, and it’s the #1 reason studies get rejected. For example, if a drug has a half-life of 8 hours, the washout must be at least 40 hours. For a drug like warfarin (half-life ~40 hours), that’s a full 7-day break. Studies often use longer washouts just to be safe. You can’t guess this-you need data from pharmacokinetic studies or published literature to prove the washout works.What Happens When the Drug Is Highly Variable?

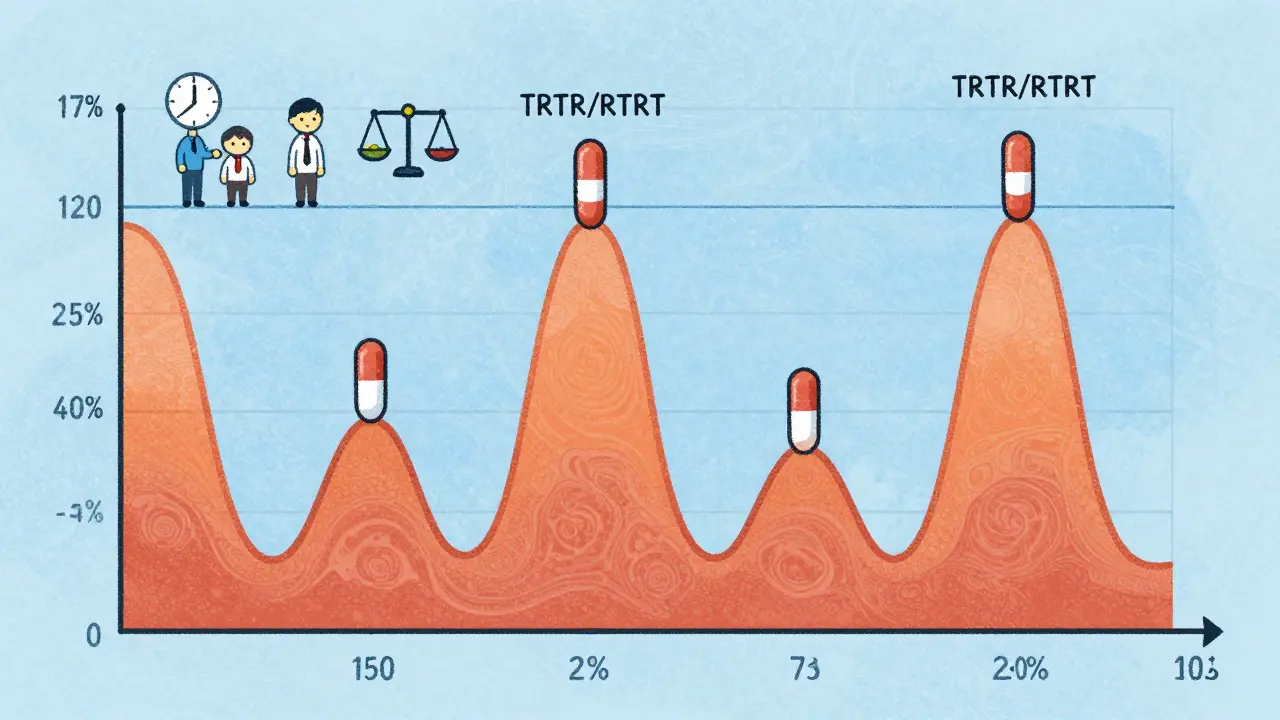

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or clopidogrel, show huge differences in how people absorb them-even the same person on the same dose can have wildly different blood levels. These are called highly variable drugs (HVDs), defined by an intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) over 30%. Standard 2×2 designs fail here. You’d need hundreds of people to get reliable results. That’s expensive and unethical. So regulators allow replicate designs: more periods, more doses per person. There are two main types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Participants get the test drug twice and the reference once (or vice versa). This gives enough data to estimate within-subject variability for the test drug.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Each drug is given twice. This lets you estimate variability for both test and reference.

How Bioequivalence Is Proven: The 90% CI Rule

It’s not about average levels. It’s about the range. After collecting blood samples over time, researchers calculate two key values: AUC (total drug exposure) and Cmax (peak concentration). The test drug is considered bioequivalent if the 90% confidence interval for the geometric mean ratio (test/reference) falls between 80.00% and 125.00% for both AUC and Cmax. That’s the universal rule for most drugs. For HVDs using RSABE, the limits aren’t fixed. They expand based on the reference drug’s variability. The math is complex, but the goal is simple: if the reference drug itself swings wildly in the body, it’s unfair to demand the generic match it perfectly. The system allows flexibility without sacrificing safety. Statistical analysis uses mixed-effects models-usually in SAS or R. The model checks for three things: sequence effect (did order matter?), period effect (did time affect results?), and treatment effect (did the drug make a difference?). If the sequence-by-treatment interaction is significant, carryover is likely, and the study fails.When Crossover Designs Don’t Work

Crossover isn’t magic. It fails when the drug’s half-life is too long. If a drug takes 14 days to clear, a 5-half-life washout means 70 days between doses. No volunteer will stay in a study for 140 days. That’s when parallel designs take over. Also, if the condition being treated is chronic-like hypertension or depression-switching drugs mid-study could be dangerous. You can’t just stop someone’s blood pressure med for a week to test a generic. Crossover is only for drugs where short-term withdrawal is safe and reversible. And then there’s human error. In 2018, about 15% of failed bioequivalence submissions were due to inadequate washout periods. One company skipped a full 7-day washout for a drug with a 40-hour half-life. Residual drug lingered. The second period results were garbage. They had to restart with a replicate design-costing nearly $200,000 more.

Real-World Impact: Cost, Time, and Success Rates

A clinical trial manager in Texas saved $287,000 and eight weeks by using a 2×2 crossover for a generic warfarin study. Instead of 72 volunteers, they only needed 24. That’s not just efficiency-it’s accessibility. Without crossover designs, many generics would never make it to market. But replicate designs aren’t cheap. They add 30-40% to study costs because of extra blood draws, longer stays, and more lab work. Yet they prevent 68% of failures for HVDs, according to a 2022 industry survey. That’s a trade-off companies are willing to make. Today, 89% of generic drug approvals in the U.S. use crossover designs. The trend is shifting: replicate designs are growing at 15% per year. In 2015, only 12% of HVD approvals used RSABE. By 2022, that jumped to 47%. The future isn’t just crossover-it’s smarter crossover.What’s Next for Crossover Trials?

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now allows 3-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs (like lithium or digoxin), where even tiny differences can be dangerous. The EMA is expected to make full replicate designs the default for all HVDs in 2024. New tools are emerging too. Adaptive designs let researchers re-calculate sample size mid-study based on early data. In 2018, only 8% of submissions used this. By 2022, it was 23%. That’s a sign the field is maturing. Some experts wonder if continuous glucose monitors or wearable sensors will one day replace blood draws altogether. Imagine tracking drug levels in real time-no washout needed. But for now, the crossover design remains the most reliable, regulated, and proven method to ensure generics are safe and effective.At its core, the crossover trial design isn’t about complexity. It’s about fairness. It gives every volunteer a chance to experience both drugs. It gives regulators confidence. And it gives patients access to affordable medicines without compromising safety.

What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control, eliminating variability between individuals. This dramatically increases statistical power and allows researchers to use far fewer volunteers-often one-sixth the number needed in a parallel design-while still getting reliable results.

Why is a washout period necessary in a crossover study?

The washout period ensures that any remaining drug from the first treatment is fully cleared from the body before the next treatment begins. If not, residual drug levels can interfere with measurements in the second period, causing carryover effects that invalidate results. Regulators require at least five elimination half-lives between periods.

What is a replicate crossover design and when is it used?

A replicate crossover design administers each drug more than once-commonly using 4 periods (TRTR/RTRT or TRR/RTR). It’s used for highly variable drugs (intra-subject CV >30%) where standard 2×2 designs lack precision. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts acceptance limits based on the reference drug’s variability.

How is bioequivalence statistically determined?

Bioequivalence is determined by calculating the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means of key pharmacokinetic parameters-AUC and Cmax-between the test and reference drug. For most drugs, this interval must fall entirely within 80.00% to 125.00%. For highly variable drugs, wider limits may be allowed under RSABE.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (e.g., over two weeks) because the required washout period would be too long for volunteers to tolerate. They’re also avoided for chronic conditions where stopping treatment could be dangerous. In these cases, parallel designs are preferred.

Stewart Smith, December 31, 2025

So basically, they’re letting one person be their own control group? That’s genius. Like testing two coffee brands on yourself instead of forcing 100 people to drink one each. Saves money, time, and doesn’t turn volunteers into human lab rats.

Also, 80% fewer people? That’s not efficiency-that’s magic.

Retha Dungga, December 31, 2025

Bro the washout period is everything 😭 I mean imagine taking your generic pill and then 3 hours later your body’s still buzzing from the brand… that’s not bioequivalence that’s just chaos 🤪

Sara Stinnett, January 1, 2026

Let me guess-this ‘crossover design’ is just a fancy way of letting Big Pharma off the hook. You’re telling me a $5 pill is ‘equivalent’ to a $50 one because a dozen people took it in a lab and didn’t hiccup? What about real-world variability? What about gut microbiomes? What about people who take it with tea vs. milk vs. whiskey?

This isn’t science-it’s statistical sleight of hand. The 80-125% range is a joke. That’s a 56% swing. If your blood pressure med swings that wildly, you’re not getting treated-you’re playing Russian roulette with your arteries.

linda permata sari, January 3, 2026

OMG I just realized-this is why my cousin’s generic warfarin didn’t work at first 😭 She was on a 5-day washout but the drug’s half-life is 40 hours… so she needed 7 days. They didn’t tell her. She almost bled out. This isn’t just about stats-it’s about lives.

Thank you for explaining this so clearly. I’m crying happy tears now.

Brandon Boyd, January 4, 2026

THIS IS WHY GENERIC DRUGS WORK. This isn’t just clever math-it’s human-centered science. Every volunteer gets both drugs. No one’s left out. No one’s a control group guinea pig. And that’s the beauty of it.

Stop thinking of it as a loophole. Think of it as a win-win-win: cheaper meds, faster approvals, safer outcomes. This is how you make healthcare accessible without sacrificing quality. Keep pushing this model, folks. It’s the future.

Paul Huppert, January 5, 2026

Wait, so if a drug has a 40-hour half-life, you need 200 hours washout? That’s 8+ days. So for warfarin, you’re basically asking someone to go off blood thinners for over a week? Isn’t that risky?

Hanna Spittel, January 7, 2026

They’re lying. The FDA just lets generics in because they’re bribed by pharma. That’s why the limits are so wide. You think they care if you die? Nah. They care if the stock price goes up 💸

Brady K., January 7, 2026

Let’s not romanticize this. The 2×2 crossover is elegant, sure-but it’s a statistical fantasy dressed in white coats. You’re assuming linearity, homogeneity, no carryover, perfect compliance. Real humans? They forget pills. They drink grapefruit juice. They sleep 3 hours. The model assumes a lab rat with a schedule. The real world? It’s messy. RSABE is a band-aid on a hemorrhage.

And don’t get me started on the SAS code. If you don’t know how to handle random effects properly, your CI is just a fortune cookie.

Kayla Kliphardt, January 8, 2026

Can someone clarify-when they say ‘five half-lives’ for washout, is that always enough? Or are there cases where even that’s not sufficient? I’m trying to understand the edge cases.

John Chapman, January 10, 2026

THIS IS WHY WE NEED MORE OF THIS. Stop wasting money on 72-person trials. This is the future. Smarter. Faster. Cheaper. And it works. The data doesn’t lie. If you’re still skeptical, go read the 2022 industry survey. 68% fewer failures with replicate designs. That’s not luck-that’s engineering. Let’s celebrate the nerds who made this happen 🙌💊