When your blood sugar drops too low, your body doesn’t just feel off-it can start to shut down. You might shake, sweat, or feel confused. In severe cases, you could pass out or have a seizure. This isn’t just a scare-it’s hypoglycemia, and it’s one of the most common and dangerous complications of diabetes treatment. Around 47% of people with Type 1 diabetes and 33% of those on insulin for Type 2 diabetes experience it at least once a year. The good news? Most episodes are preventable-and treatable-if you know what to look for and what to do.

What Counts as Low Blood Sugar?

Hypoglycemia is defined as a blood glucose level below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) for people with diabetes. The NHS in the UK uses a slightly higher threshold of 4 mmol/L (72 mg/dL) to trigger treatment. For someone without diabetes, low blood sugar is considered below 55 mg/dL (3.1 mmol/L). But numbers alone don’t tell the whole story. Some people feel symptoms at 70 mg/dL, while others don’t notice anything until it’s below 50 mg/dL. That’s because your body adapts-and sometimes, it forgets to warn you.How Do You Know You’re Having a Low?

Symptoms fall into two categories: physical (adrenergic) and mental (neuroglycopenic). The first group comes from your body’s stress response. You might feel your heart racing, your hands trembling, or sweat pouring out-even if the room is cold. These are signs your body is releasing adrenaline to try and raise your blood sugar. The second group is more dangerous. That’s when your brain doesn’t get enough glucose. You might get blurry vision, feel dizzy, or struggle to speak clearly. At 50 mg/dL or lower, confusion sets in. Below 45 mg/dL, you can lose consciousness. Seizures can happen if it drops even further. This is why hypoglycemia is often mistaken for intoxication or a stroke-especially in public. People with long-term diabetes often lose these warning signs. About 25% of Type 1 patients develop hypoglycemia unawareness after 15+ years. They don’t shake or sweat anymore. Their first symptom? Passing out. That’s why continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are so critical-they give you data before your body does.What Causes Low Blood Sugar?

For people with diabetes, three things cause most episodes:- Too much insulin (73% of cases): Taking your usual dose but eating less, or injecting too much by mistake.

- Not enough carbs (19%): Skipping meals, eating smaller portions, or not adjusting for activity.

- Unexpected exercise (9%): A walk, a workout, or even cleaning the house can drop glucose fast if insulin isn’t lowered.

What to Do When Blood Sugar Drops

If you’re alert and able to swallow, follow the 15-15 rule:- Consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbs: 4 glucose tablets, 1/2 cup of juice, 1 tablespoon of honey, or 6 hard candies.

- Wait 15 minutes.

- Check your blood sugar again.

Preventing Low Blood Sugar

Prevention is better than treatment. Here’s how to cut your risk:- Match carbs to insulin: If you take 1 unit of insulin for every 10-15 grams of carbs, stick to that ratio. Don’t guess.

- Adjust for activity: If you’re going to exercise for more than 45 minutes, reduce your basal insulin by 20-50% or eat extra carbs before and during.

- Use a CGM: Devices like Dexcom or Freestyle Libre show real-time trends. Set alerts at 70 mg/dL and 55 mg/dL. Some systems, like the Guardian 4 or Tandem Control-IQ, can automatically pause insulin delivery if your glucose is dropping too fast.

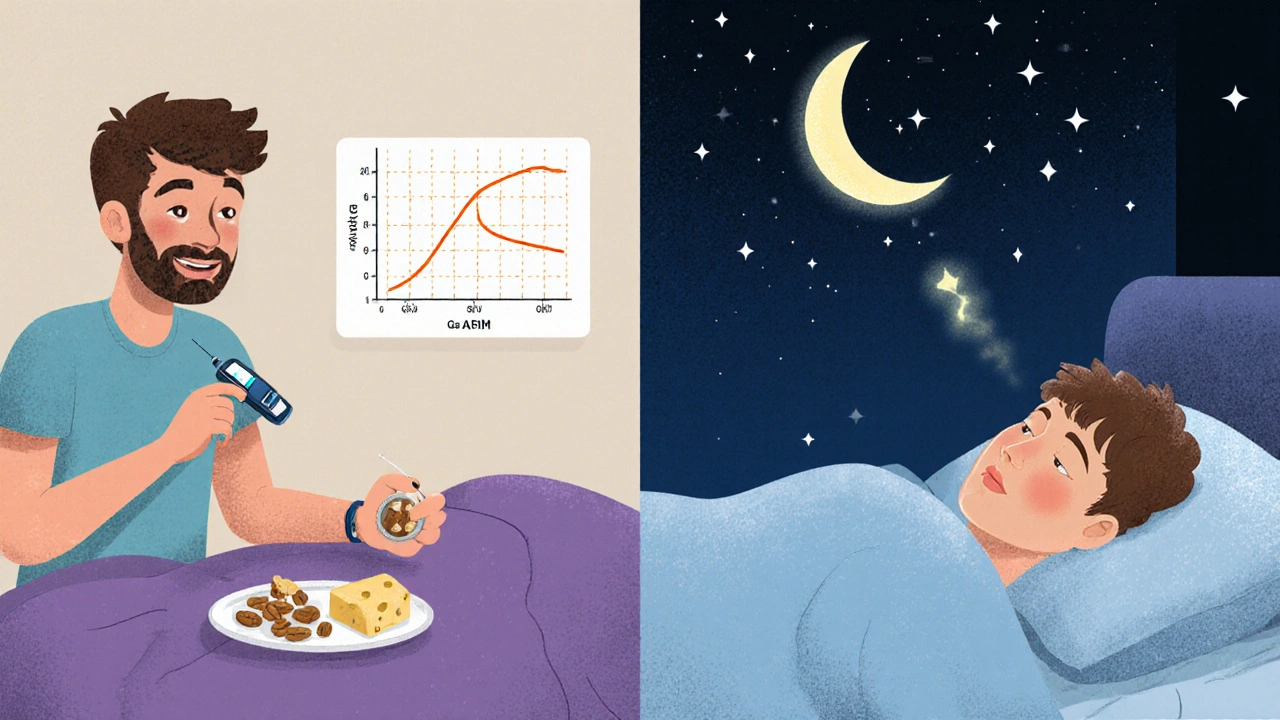

- Check before bed: Nighttime lows are the most dangerous. Aim for a bedtime glucose above 80 mg/dL. If it’s below 100 mg/dL, eat a small snack with protein and fat-like cheese or nuts.

- Wear medical ID: A bracelet or necklace that says “Diabetic-Insulin Dependent” can save your life if you’re found unconscious.

Technology Is Changing the Game

In 2023, the FDA approved Dasiglucagon (Zegalogue), a nasal powder that works faster and more reliably than older glucagon injections. The first closed-loop “artificial pancreas” systems, like Tandem Control-IQ, now reduce time spent below 54 mg/dL by over 3 hours per week. CGM adoption has jumped from 12% in 2017 to 67% in 2023 among insulin users. That’s led to a 29% drop in hospital visits for hypoglycemia. But tech isn’t perfect. Sensor lag can miss rapid drops-some users report readings 40 mg/dL higher than actual blood sugar during fast declines. Always confirm with a fingerstick if you feel symptoms but the CGM says you’re fine.Who’s at Highest Risk?

- Type 1 diabetes: Average of 19 episodes per month. Most are mild, but the risk of severe lows is highest. - Elderly patients (>65): Often show atypical symptoms-falls, confusion, dizziness-mistaken for dementia. Each severe episode raises dementia risk by 4.7%. - People with hypoglycemia unawareness: 6-fold higher risk of death. - Those on multiple daily injections or pumps: More insulin flexibility means more room for error.

What Not to Do

- Don’t ignore mild symptoms. A 65 mg/dL reading might seem “fine,” but cognitive impairment starts here. Driving at 50 mg/dL is like driving with a 0.08% blood alcohol level. - Don’t over-treat. Eating a whole bag of candy to fix a 60 mg/dL low can send your sugar soaring, leading to rebound highs. - Don’t assume your symptoms are the same every time. Studies show 37% of people experience different signs from one episode to the next. - Don’t wait to train others. If you live alone, teach a neighbor or friend how to use glucagon. Keep a written instruction sheet in your wallet.When to Call for Help

Call 999 or go to A&E if:- You or someone else is unconscious or having a seizure.

- Glucagon was given but there’s no improvement after 15 minutes.

- You’ve had two or more severe lows in one week.

- You’re unsure whether it’s hypoglycemia or something else-many ER visits are misdiagnosed as strokes.

Final Thoughts

Hypoglycemia isn’t a failure-it’s a signal. It tells you your treatment plan needs tweaking. With the right tools-CGMs, glucagon, carb counting, and education-you can live without fear of low blood sugar. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s awareness. It’s preparation. It’s knowing what to do before your body screams for help.What is the normal blood sugar range for someone with diabetes?

For most people with diabetes, a normal fasting blood sugar is between 80-130 mg/dL before meals, and under 180 mg/dL two hours after eating. Hypoglycemia is defined as a drop below 70 mg/dL, which requires immediate action. The NHS uses 4 mmol/L (72 mg/dL) as the treatment threshold.

Can non-diabetics get hypoglycemia?

Yes, but it’s rare. Reactive hypoglycemia can happen after meals, especially after weight-loss surgery. Fasting hypoglycemia may point to serious conditions like insulinoma (a tumor), liver disease, or adrenal insufficiency. If you’re not diabetic and keep having low blood sugar, see a doctor for testing.

Why do I get low blood sugar at night?

Nighttime lows happen because insulin doesn’t stop working while you sleep. If your basal rate is too high, or you ate less than usual at dinner, your glucose can drop. Exercise during the day, alcohol, or skipping a bedtime snack can also contribute. Using a CGM with a low alert set at 65-70 mg/dL can help catch them before you wake up.

Is it safe to drive with diabetes?

Yes-but only if your blood sugar is above 70 mg/dL. At 50 mg/dL, your reaction time and judgment are as impaired as someone with a 0.08% blood alcohol level. Always check your glucose before driving. Keep fast-acting carbs in the car. If you feel symptoms while driving, pull over immediately.

How do I know if I have hypoglycemia unawareness?

If you’ve had several low blood sugar episodes without feeling the usual warning signs like shaking, sweating, or a racing heart, you may have hypoglycemia unawareness. It’s common after 15+ years of Type 1 diabetes. A CGM can help detect lows you don’t feel. Talk to your doctor-adjusting insulin targets slightly higher for a few weeks can sometimes restore your body’s warning system.

Can I use candy or chocolate to treat low blood sugar?

Not ideal. Chocolate and candy contain fat, which slows sugar absorption. Glucose tablets, juice, or honey work faster because they’re pure sugar. If you’re in a pinch, use what’s available-but follow up with a balanced snack once your sugar is back up.

Does glucagon expire?

Yes. Most glucagon kits expire in 1-2 years. Check the date on the package. Nasal glucagon lasts longer than injectable versions. Store it at room temperature. If you’re unsure whether it’s still good, replace it-there’s no room for error in an emergency.

What should I do if my CGM shows a low but I don’t feel symptoms?

Always confirm with a fingerstick test. CGMs can lag, especially during rapid glucose drops. If your fingerstick shows 68 mg/dL and you feel fine, eat a small snack with protein and carbs. Don’t ignore it. Over time, ignoring alerts can train your body to stop warning you.

Latrisha M., November 16, 2025

Knowing the signs and having glucagon on hand saved my brother’s life last year. I wish every family had this info. Simple, life-saving stuff.

Jamie Watts, November 17, 2025

Look I’ve been diabetic for 18 years and I still see people saying juice is the answer. No. Glucose tabs are the only thing that work fast. Candy? Fat slows it down. You’re not helping anyone by giving them a chocolate bar. Learn the science.

Deepak Mishra, November 18, 2025

OMG I just had a low at 3am and my CGM said 72 but I was DIZZY and sweating and I thought I was dying 😭😭😭 then I checked with a strip and it was 58... I’m never ignoring my body again

Ankit Right-hand for this but 2 qty HK 21, November 20, 2025

This whole article is propaganda pushed by Big Pharma. CGMs cost 1000 a month. Glucagon? You need a prescription. Meanwhile your insulin costs 300. Who benefits? Not you. They want you dependent. Real solution? Stop insulin. Eat real food. Stop the lies

Oyejobi Olufemi, November 21, 2025

Oh, so now we’re supposed to trust machines? CGMs? They’re unreliable! I’ve had readings that were 40 points off-do you know what that means? You could die from overtreating! And glucagon? It’s a chemical trap. Your body doesn’t need synthetic hormones. Natural healing. Eat more fat. Stop the fear. You’re being manipulated.

Teresa Smith, November 22, 2025

It’s heartbreaking how many people don’t know the difference between a low and a stroke. I’ve seen someone collapse at a grocery store and no one knew what to do. That’s why education matters-not just for diabetics, but for everyone. A five-minute conversation could save a life. Don’t wait for a crisis to learn this. Teach your kids. Tell your coworkers. Share this. It’s not medical jargon-it’s basic human survival.

David Rooksby, November 22, 2025

Let’s be real here-why does the FDA keep approving new glucagon sprays when the old ones work fine? And why is everyone suddenly obsessed with closed-loop systems? It’s not about safety-it’s about profit. The diabetes industry is a billion-dollar machine that thrives on fear. If you’re constantly told you’re one low away from death, you’ll keep buying devices, sensors, and emergency kits. But here’s the truth: most people who die from hypoglycemia are elderly, isolated, or on multiple daily injections with no support. The real fix isn’t tech-it’s community. Someone checking in. Someone knowing your name. Someone who knows where your glucagon is. That’s what saves lives-not another app.

Daniel Stewart, November 23, 2025

There is an existential paradox in hypoglycemia: the body’s most primal survival mechanism-the fight-or-flight response-is simultaneously the very system that fails to warn us when it matters most. We are biological machines that evolved to detect scarcity, yet modern insulin therapy has inverted the natural feedback loop. The brain, starved of glucose, does not scream-it surrenders. And so we become strangers to our own physiology. Awareness is not a tool. It is a reclamation of self.

Dan Angles, November 23, 2025

Thank you for this comprehensive, evidence-based overview. I appreciate the inclusion of both clinical thresholds and real-world behavioral recommendations. Particularly valuable is the emphasis on training non-medical personnel in glucagon administration. This is not merely a personal health issue-it is a public health imperative. I have distributed this resource to my local diabetes support group and encourage all providers to do the same.

ZAK SCHADER, November 23, 2025

Why is everyone so obsessed with glucose tabs? In my country we just eat sugar cubes. Works fine. And why do we need fancy devices? My grandpa had diabetes in 1950 and he lived to 92. No CGM. Just sugar and discipline. America overcomplicates everything.

Danish dan iwan Adventure, November 24, 2025

Hypoglycemia unawareness is a clinical entity classified under autonomic neuropathy. It correlates with prolonged hyperglycemic exposure and insulin titration without glycemic variability monitoring. CGMs mitigate risk via predictive algorithms and trend arrows. Basal rate optimization reduces nocturnal incidence by 40–60%. Adherence to 15-15 rule remains gold standard. Glucagon nasal formulation has bioavailability of 87% vs 85% for IM. Data robust.

Diane Tomaszewski, November 25, 2025

I used to think lows were just part of having diabetes. Then I started checking my sugar before I drove, before I went to bed, before I played with my kids. It’s not about being perfect. It’s about being present. Small changes make all the difference.

John Mwalwala, November 26, 2025

Did you know the government and Big Pharma are secretly using CGMs to track your glucose levels and sell your data to insurance companies? They want to raise your premiums based on your blood sugar spikes. And glucagon? It’s laced with microchips. That’s why they push it so hard. Don’t trust the system. Use honey. Avoid insulin. Stay off the grid. Your body knows better than any machine.