When you pick up a generic version of your prescription drug and pay a fraction of what the brand-name version costs, you’re benefiting from a decades-long legal battle fought in courtrooms, not pharmacies. Behind every cheap pill is a web of patents, lawsuits, and landmark court decisions that decide who can sell what, and when. This isn’t just legal jargon-it’s what keeps life-saving medications affordable or locks them behind expensive monopolies.

How Generic Drugs Break Patent Monopolies

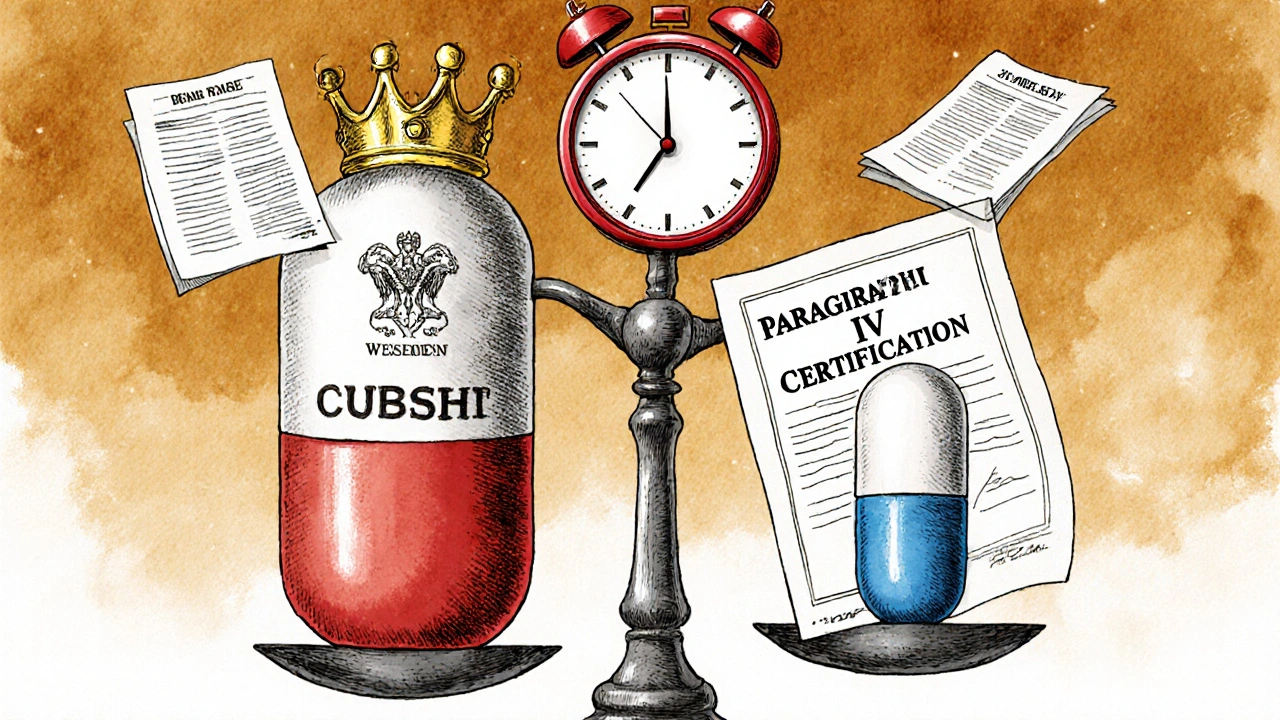

The system that lets generics enter the market was built by Congress in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. It was designed as a compromise: give brand-name drug makers extra time to recoup R&D costs, but create a clear path for cheaper copies to follow. The key tool? The ANDA-Abbreviated New Drug Application. Generic companies don’t have to repeat expensive clinical trials. Instead, they prove their drug is the same as the brand. But here’s the catch: they must challenge any patents listed in the Orange Book, the FDA’s official registry of drug patents. If a generic maker files a Paragraph IV certification, they’re saying, “This patent is invalid or we don’t infringe it.” That triggers a 30-month legal freeze on the generic’s launch. The brand company sues. The clock starts ticking. And that’s where the real battle begins-not in the lab, but in court.Amgen v. Sanofi: The End of Overly Broad Biologic Patents

In 2023, the Supreme Court ruled in Amgen v. Sanofi that patents claiming “millions of possible antibodies” based on just 26 real examples were invalid. Why? Because the patent didn’t teach others how to make the rest. It was like claiming you invented all cars because you built one with a V8 engine and a red paint job. This decision hit biologic drugs hard. These are complex, protein-based medicines like Humira or Enbrel. Before this case, companies could patent huge, vague families of molecules. Now, they must clearly describe how to make each version. The result? More than 120 biologic patents have been challenged since, and 68% of those were narrowed or thrown out. Generic makers are breathing easier. But some experts warn it could slow innovation in next-gen therapies.Allergan v. Teva: Protecting the First-to-File Advantage

In 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled in Allergan v. Teva that a patent filed later can’t be used to invalidate an earlier one-even if the later patent expires first. This might sound technical, but it’s huge. Brand companies used to file multiple patents on minor changes (like a new pill coating or dosage timing) to stretch their monopoly. The court said: no. Only the first patent on the actual drug matters. This decision strengthened the value of early, core patents. It also made “patent thickets” harder to build. Generic companies now have clearer targets. Instead of fighting 15 overlapping patents, they can focus on the one that really counts. For patients, that means fewer delays.

Amarin v. Hikma: When Marketing Becomes Infringement

Here’s a sneaky tactic brand companies use: they don’t sue over the drug itself. They sue over the label. In Amarin v. Hikma, the brand company claimed the generic’s marketing materials suggested off-label uses-even though the generic’s label didn’t include them. The court agreed. The generic’s website and sales reps had hinted at uses not approved by the FDA. That’s called “induced infringement.” It’s a gray area. Generic makers can’t say their drug treats something the brand drug does, if it’s not on the official label. But they also can’t stay silent. The result? A legal minefield. In 2023, 63% of induced infringement claims by brand companies succeeded. That’s why generic firms now hire legal teams just to review their website copy.How the System Works Today

As of 2024, 85% of U.S. prescriptions are filled with generics. But getting there isn’t easy. The average Hatch-Waxman lawsuit lasts nearly 29 months. The first generic company to challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market access-no other generics can enter. That’s a huge incentive. But it also creates pressure. Companies rush to file, sometimes without solid evidence. The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has become a key battleground. In 2023, 78% of generic challenges used IPRs-faster, cheaper proceedings that can kill patents without a full court trial. The result? More patents get invalidated before they even reach district court. But brand companies are adapting. They’re filing more patents, earlier, and in more countries.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The FDA is cracking down on “evergreening.” New rules proposed in early 2025 require patent holders to prove their listed patents are directly tied to the drug’s active ingredient-not just packaging or dosing. That could knock out hundreds of low-quality listings. Biosimilars-generic versions of biologic drugs-are the next frontier. In 2024, they made up 27% of patent disputes. That number is expected to hit 31% by 2027. But these cases are more complex. They require deep science knowledge, not just legal skill. A single biosimilar lawsuit can cost over $10 million. And patients? They’re feeling the squeeze. One Reddit user shared that their insulin alternative was delayed 22 months due to patent litigation-costing them $8,400 out-of-pocket. The FTC estimates unresolved patent disputes will delay $127 billion in generic savings through 2026. Cardiovascular and cancer drugs are the worst offenders.What You Need to Know

If you’re a patient, you’re not powerless. Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a generic available?” If they say no, ask why. Often, it’s a patent issue-not a science one. If you’re a student or new attorney entering this field, start with the Orange Book. Learn how to read patent listings. Understand Paragraph IV certifications. Master the difference between a formulation patent and a method-of-use patent. The law isn’t static. Every year, new rulings shift the balance. The courts are trying to protect innovation without blocking competition. But the system is still tilted. Brand companies have teams of lawyers, patent agents, and regulatory experts. Generic makers are often small firms fighting giants. The real win? When a patent is invalidated, prices drop 80-85% within a year. That’s not just business. That’s public health.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act and why does it matter for generic drugs?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created the legal framework for generic drugs to enter the market without repeating costly clinical trials. It lets generic companies challenge patents via Paragraph IV certifications, triggering lawsuits that can delay or accelerate market entry. It balances innovation incentives for brand companies with faster access to affordable medicines for patients.

What is the Orange Book and how does it affect generic drug approval?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of approved drug products and their associated patents. Generic manufacturers must review this list and certify whether they’re challenging any listed patents. If they do, it triggers a 30-month legal stay on their product launch. Accurate Orange Book listings are critical-mislisting patents can lead to lawsuits or regulatory penalties.

What’s the difference between a Paragraph IV certification and a Paragraph III certification?

A Paragraph III certification means the generic company agrees to wait until all patents expire before launching. A Paragraph IV certification is a legal challenge: the generic says the patent is invalid or they won’t infringe it. Only Paragraph IV filings trigger lawsuits and the 30-month stay. These are the filings that lead to landmark court cases.

Why do generic drug lawsuits take so long?

Hatch-Waxman cases are complex, involving technical science, patent law, and regulatory rules. Courts often need expert testimony on chemical structures, pharmacokinetics, and manufacturing processes. The average case lasts 28.7 months. Many drag on because brand companies file multiple patents, forcing generics to challenge each one separately.

Can a generic drug company be sued even if they don’t infringe the patent?

Yes. Courts have ruled that marketing materials, website content, or sales rep statements suggesting unapproved uses can constitute “induced infringement.” Even if the label is correct, if the generic promotes off-label uses that the brand patent covers, they can still be sued. This is why many generics hire legal teams just to review their advertising.

How do biosimilars differ from traditional generics in patent disputes?

Biosimilars are copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells, not chemicals. They’re harder to replicate exactly, so the law treats them differently. Unlike traditional generics, biosimilars must go through a “patent dance”-a mandatory exchange of patent information with the brand company. Disputes often involve whether the biosimilar is truly “similar enough,” and whether patents cover manufacturing processes rather than the drug itself.

What role does the PTAB play in generic patent cases?

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) handles inter partes reviews (IPRs), which are faster, cheaper alternatives to district court litigation. In 2023, 78% of generic challengers used IPRs to try to cancel patents before going to court. IPRs have invalidated over 60% of challenged biologic patents since 2020, making them a critical tool for speeding up generic access.

Robin Johnson, November 24, 2025

This is why I hate how pharma runs the system. They don't innovate-they just tweak a pill and sue everyone who tries to make it cheaper. I had to pay $700 for my blood pressure med last year. This year, the generic hit and it's $22. No magic. Just law. And they still fight it.

Latonya Elarms-Radford, November 25, 2025

Let us not forget the metaphysical weight of intellectual property in the neoliberal pharmacopoeia-where the commodification of biological knowledge becomes a sacrament of capital, and the patient, reduced to a mere consumer of molecular relics, is left to navigate the labyrinthine liturgies of patent clerks and corporate theologians. The Orange Book is not a registry-it is a scripture written in the blood of the uninsured, and every Paragraph IV certification is a heretical whisper against the altar of monopoly. The courts, in their infinite wisdom, have become the high priests of this sacred economy, blessing the few and cursing the many with the sacrament of affordability-or the damnation of co-pays. Amgen v. Sanofi? A minor heresy. A flicker. The true heresy is that we still believe in the myth of innovation when what we're really selling is legal delay wrapped in the skin of science.

Mark Williams, November 27, 2025

Interesting how PTAB IPRs have become the de facto first line of defense for generics. The stats are clear-60%+ invalidation rates on biologic patents since 2020. But what's rarely discussed is the strategic timing: most IPRs are filed within 90 days of ANDA submission. That’s not coincidence-it’s a calibrated legal tactic. The brand companies know this, which is why they’re now filing provisional patents earlier, sometimes even before Phase 3 trials finish. It’s a race to the IP fence line. The real bottleneck isn’t science-it’s procedural leverage.

David Cunningham, November 28, 2025

Man, I live in Australia and we don't have this mess. Our PBS just negotiates prices outright. If a drug’s too expensive, they don’t wait for a lawsuit-they just say no. We still get generics, just not after a 2-year court battle. Kinda makes the US system look like a glitchy software update.

luke young, November 29, 2025

Really appreciate this breakdown. I used to think generics were just cheap knockoffs, but now I see how much legal strategy goes into it. The Paragraph IV thing is wild-like a legal grenade you throw to blow up a patent. And the whole induced infringement thing with marketing? That’s next-level. Makes me wonder how many people are getting scared off from even trying to make cheaper meds because the legal risk is so high.

james lucas, November 30, 2025

bro the hatch-waxman act is kinda like a truce in a war where both sides are cheating. brand companies file 20 patents on the same pill just to keep people from making the cheap version. and then the generics go to court and its like 5 years later and the patent was gonna expire anyway. i had a friend who worked at a generic pharma co and they said half their legal team just reads the orange book and looks for dumb patents. like ‘patent for blue pill instead of white’-and they’re like ‘yep, lets challenge that’.

Jessica Correa, November 30, 2025

the part about biosimilars being way more complicated is so true. its not like making a copy of aspirin. these are living drugs. the body reacts differently. but the patents are so vague its like saying ‘we invented all dogs because we made a golden retriever’. and then the lawsuits cost millions. i know someone who lost their job because their company got sued over a biosimilar label and they had to shut down the whole project. its not just about money its about people

manish chaturvedi, November 30, 2025

As a physician from India, I have witnessed firsthand the life-saving impact of generic drugs in low-resource settings. The Hatch-Waxman framework, though American in origin, has inspired similar regulatory models across the Global South. However, the aggressive patent litigation tactics described here are increasingly exported through trade agreements. We must be vigilant: access to medicine is not a privilege to be auctioned in courtrooms, but a fundamental human right. The Supreme Court’s decision in Amgen v. Sanofi was a moral victory-not merely a legal one. Let us hope that future rulings prioritize patients over patents.